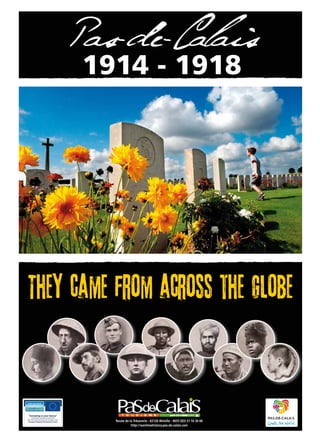

1914 18 - they came from across the globe

- 1. Route de la Trésorerie - 62126 Wimille FRANCE - 0033 (0)3 21 10 34 60 http://wartimehistory.pas-de-calais.com Pas-de-Calais 1914 - 1918 They came from across the globe Pas-de-Calais

- 2. 2 Access and useful information : A list of our tourist offices is available from www.visit-pas-de-calais.com Scan the QR code for an online list of tourist offices By car : A16, A25 and A26 motorways along the coast or inland From Great Britain: - Eurotunnel : Folkestone – Calais (35mn) www.eurotunnel.com - DFDS Seaways : Dover – Calais (1h30) www.dfdsseaways.com - P&O Ferries : Dover – Calais (1h30) www.poferries.co.uk (foot passengers accepted) By train : - Eurostar : London / Paris / Brussels / Lille – Calais Frethun www.eurostar.com - French national railways (SNCF) www.voyage-sncf.com - TER Regional railways www.ter-sncf.com By plane : Le Touquet airport 00333 21 05 03 99 – www.aeroport-letouquet.com Editorial During the Great War, the Pas- de-Calais was at the heart of a world conflict: the British, Belgians, Canadians, New Zealanders, Poles, Czechs, Portuguese, Native Americans, Senegalese, Indians and Chinese were just some of the nationa- lities who fought in our region. Thousands of letters written by young soldiers left the Pas-de- Calais département daily to make their way to countries dotted around the world. Bearing witness to these bloody battles, the largest cemetery in France is situated in Notre- Dame-de-Lorette, in the com- mune of Ablain-Saint-Nazaire, while the largest British military cemetery in France is found in Etaples. The Musée Jean et Denise Letaille has recently been opened in Bullecourt in tribute to the sacrifice made by the Diggers, a nickname given to the brave Australian soldiers – 10,771 in total – who were killed on the battlefields in this area. However, looking beyond this tragic conflict, it should be emphasised that the Pas-de- Calais made courageous efforts to get back on its feet in the post- war period – with the help of the French nation, more than a hundred towns and villages were rebuilt. Today, with an emphasis on sustainable development, the Conseil Général (county council) of the Pas-de-Calais départe- ment is looking to improve these memorial sites, so that as many visitors as possible can visit them and learn more about this period of history. It is with this in mind that the council is taking part in the Euro-regional “Memories of the Great War” programme along with the Belgian province of West Flanders and the French départements of Nord, Aisne and Somme, as well as being involved in the promotion of the Remembrance Trails started by the Nord-Pas de Calais regional council. On a day-to-day basis, it seems important to me not to restrict ourselves to simply evoking the facts. We must also, and above all, emphasise the barbarity of this conflict so that we give our young people an overwhelming desire to maintain and promote peace. • P. 3 - International cemeteries and memorials • P. 4 - The Great War in the Pas-de-Calais • P. 5 - Morrocans, Algerians, Tunisians... From Africa to the Artois… • P. 6 - French • P. 7 - Émilienne Moreau from Loos-en-Gohelle • P. 8 - English • P. 9 - A mutiny beneath a veil of silence • P. 10 - Scots, Irish • P. 11 - Americans • P. 12 - Canadians • P. 13 - The 22d Battalion «indefatigable heroism» • P. 14-15 - Map of Pas-de-Calais • P. 16 - Native Americans • P. 17 - Indians • P. 18 - Australians • P. 19 - New Zealanders • P. 20 - Japanese • P. 21 - South Africans ; Newfoundlanders ; For Belgian refugees in France • P. 22 - Portuguese • P. 23 - Poles and Czechs • P. 24 - Germans • P. 25 - The German newspaper in Bapaume • P. 26 - Chinese Contents

- 3. 3 W i m e r e u x C o m m u n a l Cemetery 6 Rue Jean Moulin, 62930 Wimereux Amongst the soldiers buried in Wimereux is Canadian L i e u t e n a n t Colonel John M c C r a e t h e author of “In Flanders Fields” (1915) on whose Memorial Seat you can read an excerpt of the most famous poem about World War I: “We are the dead. Short days ago, We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, Loved and were loved and now we lie In Flanders fields” The poppy and the cornflower The poppy mentioned in the poem “In Flanders Fields” by John McCrae has symbo- lised the remembrance of fallen soldiers from the Commonwealth since the First World War. Since 1916, the cornflower (“bleuet” in French) has been the symbol in France of solidarity with war victims and veteran sol- diers. The flower’s colour recalls the blue of the French soldiers’ uniform worn at this time. St-Mary’s advanced Dressing Station Cemetery In Haisnes, near Lens At this Cemetery are almost 2,000 graves of sol- diers who perished during the Battle of Loos, of which over two-thirds are of “unknown soldiers”. Among the graves is that of Rudyard Kipling’s son John who died in the battle at the age of 18. The father spent his final years until his death in 1936 searching for the grave of his only son. John’s grave was identified in 1991, but doubts remain. The underground passages of Arras Beneath the streets of Arras lie impressive chalk quarries which have been hollowed out since the Middle Ages. Arras was destroyed in 1914. In November 1916, the Allies began their preparations for a diversionary attack on the Artois Front prior to their assault on the Chemin des Dames. The British had the ingenious idea of connecting the quarries so that Allied soldiers could emerge from this underground network and push back the front line. At 5.30am on 9 April 1917, after a huge explo- sion, 24,000 men suddenly appeared from beneath the ground and took the front German lines by surprise. At the same time, the Canadians launched an attack on Vimy Ridge. The Wellington Quarry (Carrière Wellington), a memorial to the Battle of Arras, allows visitors to learn more about this major event of the First World War. Rue Delétoille 62000 Arras Tel : 00 33 (0)3 21 51 26 95 www.explorearras.com Did you know ? International cemeteries and memorials T here are more than 600 military cemeteries in the Pas-de-Calais region. The sites bear continuing witness to the tragic events in the region during the First and Second World Wars. We cannot list here all the cemeteries in the Pas-de-Calais, so to indicate the origin of all the soldiers who died on our lands, we have decided to list one cemetery per nation. France National necropolis of Notre-Dame- de-Lorette Ablain-Saint-Nazaire Notre-Dame-de-Lorette is the largest French military cemetery. Visit the Roman-Byzantine Chapel and the Lantern Tower as well as the Ring of Remembrance, the International Memorial inaugurated on 11 November 2014. This ellipse-shaped monument brings together 580,000 names presented in alphabetical order without distinction by nationality. Commonwealth Forces Etaples Military Cemetery Etaples - RD 940 The Imperial British Army built hospitals to care for the wounded from the front around the military camp at Etaples. 10,771of the wounded died of their injuries and are buried here, in the largest cemetery for Commonwealth Forces in France with nearly 11,500 graves. Germany La Maison Blanche German military cemetery at Neuville-Saint-Vaast Neuville-Saint-Vaast – D937 road (10 min drive) The largest German war cemetery in France, it is the final resting place for 44,833 German soldiers of which 8,040 were never identified and buried in a common grave. The way the site is constructed reflects the important place that nature has in German mythology. Australia Australian memorial at Bullecourt BulLecourt – rue de Douai By 10 April 1917, when the Battle of Arras had been in progress for one day, Australian soldiers left to attack the German lines at Bullecourt. A second offensive was launched on 3 May. The statue of the Digger is a tribute to the 10,000 Australian soldiers who fell during these operations. New-Zealand New-Zealand Memorial – Grévillers British Cemetery Grévillers – RD 29 This memorial was erected in memory of the New Zealand soldiers reported mis- sing during the “100-Day Offensive” in the summer of 1918, which enabled the Allied armies to cross the German lines and libe- rate occupied territory. South Africa Warlencourt British Cemetery On the D929 towards Pozières Warlencourt -Eaucourt South-African troops arrived in France in spring 1916, and took part in a number of operations during the Battle of the Somme. In particular, 128 South-African soldiers lost their lives when taking the Butte of Warlencourt and Eaucourt l’Abbaye. Today they rest in the cemetery. Canada Canadian National History site at Vimy Ridge - Vimy On 9 April 1917, Canadian soldiers, united for the first time in a single army corps, took part in the Battle of Arras and succeeded in taking Vimy Ridge, strongly defended by the German Army. The memorial recalls this key episode in the history of the Canadian Nation, and pays tribute to the 11,285 Canadian sol- diers reported missing during the First World War.. India Neuve-Chapelle Indian Memorial, Intersection of the D947 and the D171 Richebourg l’Avoué The first Indian troops in the Imperial British Army arrived in France in October 1914. They were first stationed in Flanders and took part in the Battle of Neuve Chapelle in March 1915. This memorial is to their role in France and in Belgium during the Great War. Portugal Portuguese Military Cemetery at Neuve Chapelle Intersection of the RD 947 and the RD 171 Richebourg l’Avoué The new Republic of Portugal showed its support for France and Great Britain by sending around 56,000 soldiers to join the Allied Armies. Stationed in Flanders, the Portuguese soldiers suffered the full brunt of the offensive launched by the German Army in March 1918 in the La Lys valley. Belgium Belgian Military Square at the Communal Cemetery at Calais Boulevard de l’Egalité - Calais Belgium was almost entirely occupied by the German Army in 1914. Only the area between Ypres and Nieuport remained free. The Belgian Army was assigned to defend the front at the Yser, and set up bases in the Nord - Pas-de-Calais. China St. Etienne-au-Mont Communal Cemetery St. Etienne-au-Mont Communal Cemetery – RD 940 From 1916 onwards, the British Army recruited Chinese peasants for logistical tasks in its camps in France. At the end of the fighting, men from the Chinese Labour Corps were involved in minesweeping the land and burying soldiers who had died on the battlefield. Czechoslovakia Czechoslovak Military Cemetery and the “Nazdar” Company Memorial Neuvile Saint-Vaast – D937 towards Souchez The memorial pays tribute to Czechoslovak emigrants in Paris who enlisted in the Foreign Legion, where they formed the “Nazdar” Company to uphold the concept of a Czechoslovakia freed from the domi- nion of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Poland Polish Memorial Neuvile Saint -Vaast – RD 937 towards Souchez In 1914, the German, Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires divided Polish ter- ritory among themselves. When war broke out, Polish emigrants enlisted alongside soldiers in the French Army, hoping to see the rebirth of an independent Poland. The monument bears the words of these volunteers: “Za nasza wolnosc i wasza”. (For our freedom and yours).

- 4. 4 Text : Christian Defrance At any given moment, every community in the Pas-de-Calais had, to a greater or lesser extent, an involvement in the First World War. All had seen their youngest inhabitants head off to war; all had cried for those who had “died for France”. After the 90th anniversary of the end of the Great War, “we are witnessing a transition from living memory to history”, explains the director of La Coupole, a history and remembrance centre in the Nord-Pas de Calais region. The last surviving French soldiers of the First World War (known as “Poilus”) have now died and their voices have been replaced by photographs and the official journals of regiments – a treasure-trove of documents which has brushed aside the simplistic idea of a war involving the French, Germans and British. This war was a global war and the Pas-de- Calais represented “a microcosm of the world at war”, to quote an expression coined by the historian Xavier Boniface. A magnifying glass placed over this microcosm highlights the role played by Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders, Indians, Portuguese, Americans, South Africans and other nationalities during the conflict. The French and British put their colonies to the severest of tests – in the trenches and on the battlefields of the Pas-de-Calais. «The front developed gradually » TheFirstWorldWarinourdépartement can be divided into three phases. From late August 1914 to late October 1914, the Pas-de-Calais witnessed a war of movement: “the great German army advancing towards Paris”, and villages providing support for the mix of French and British troops. “The front developed gradually”, Yves Le Maner goes on to add. The last classic military confrontations took place in early October (Courcelles-le-Comte, Saint-Laurent-Blangy, Lorette etc), and the first battle of Ypres marked a turning-point – the end of the “Race to the Sea”. « 100% British » With the onset of this “static war” , the front line became fixed and barely moved at all, with the exception of the Hindenburg retreat. In late 1915-early 1916, the Allies were awaiting a “new army” in the form of units arriving from Canada and Australia – fresh troops which would be plunged into the bloodbath of the Somme, now that France “was committing everything it had to Verdun”. From 1916 onwards in the Pas-de- Calais, the front became “100% British”. April 1917 was to see a major offensive: victory at Vimy, defeat in Arras; and in November 1917 in Cambrai the Germans employed infantry counter-attacking techniques for the first time. Methodical advances The Russian retreat signalled a return to a war of movement. March 1918 saw Prussian elite troops go on the offensive. The Battle of the Lys forced back the British but saw the French come into their own: “the hole was filled in the nick of time”. From late August 1918 onwards, and with moral restored, the British attacked methodically and made significant advances, most notably at the Second Battle of Arras, and in the capture of the Canal du Nord (under construction since 1913) at the end of September 1918. The Great War had a huge impact on the Pas-de-Calais which went to its very core. With men arriving from around the world, it was now well and truly part of the 20th century. I f you had passed through or flown over the Pas-de-Calais at the end of 1918 when the cannons finally fell silent, you would have been aware of three distinct areas affected by a conflict which had involved all five continents. In the area by the front – where 200 communities were affected and which extended for a distance of 30-40km – nothing remained, particularly around Bapaume. Not a single tree, house or church. In the occupied (German) zone – the occupation “had been well thought out and methodical”, according to Yves Le Maner – everyday life and coal-mining were gradually re-establishing themselves. Meanwhile, in the rear zone (the Boulonnais, Montreuillois, Audomarois and Ternois areas), where millions of troops had passed through, military headquarters, hospitals and camps had all left their mark on both the land and people’s spirits. Les Échos du Pas-de-Calais BP 40139 – 5, place Jean-Jaurès 62190 Lillers - France Tél. 00333 21 54 35 75 – Fax 00333 21 54 34 89 http://www.echo62.com email : contact@echo62.com L’Echo du Pas-de-Calais is a free public newspaper delivered to the inhabitants of the Pas-de-Calais. The monthly periodical is the voice of the Pas-de-Calais and deals with a wide variety of subjects including culture and heritage, sports, tourism, wildlife, economy, arts and crafts, events, agriculture etc. “They came from across the globe” has been adapted from an original file created by Les Echos. Editor : Roland Huguet Editorial manager : Jean-Yves Vincent Executive Editor : Philippe Vincent Managing Editors : Christian Defrance Features Editor : Marie-Pierre Griffon Writer/Graphic Designer : Magali Crombez Photographer : Jérôme Pouille Sub-Editor : Claude Henneton In addition to those mentioned elsewhere, the following have contributed to the production of this publication : Michel Gravel, Hugues Chevalier, Yves Le Maner, Robert Wabinski, Alain Jacques, Dominique Faivre, Brigitte Deligne, Henri Claverie, Yann Hodicq, Raymond Sulligez, Philippe Égu. Printed by : Chartrez (62) The Great War in the Pas-de-Calais Hell, chaos and the 20th century D uring the years 1914- 18, British, Chinese and many other nationalities passed through my maternal grandmother’s house. From here, they left for the battlefield and the nearby Front – and sadly not all of them returned to collect their belongings. After the death of my grandmother in 1943, we found a collection of objects and items still waiting to be collected in one of her rooms! She would never have dreamed of touching any of these items. Our family shared these belongings amongst ourselves and I still have a small camp stove from this collection, although the “English biscuits” kept in large tins were all eaten during the Second World War – we couldn’t leave them for the Germans. You’ll find a range of photos, anecdotes and portraits of these terrible years in this special edition. This is the story, not of the battles but of those who came from all corners of the globe to fight in the Pas- de-Calais region. Their human, moving accounts strengthen our desire for peace at all times. The country which was our enemy during that war and which is now creating a new Europe alongside France also experienced horrendous casualties, many of whom were extremely young, such as the soldier who was killed at the age of 14. It is only right that our département, to which more nations sent their soldiers than any other, should dedicate the following pages to them. Roland Huguet, President of the association Les Échos du Pas-de-Calais PhotofondsdocumentaireMichelGravel

- 5. 5Text : Philippe Vincent-Chaissac Moroccans, Algerians, Tunisians... F OR the vast majority of the inhabitants of the Pas-de-Calais, the name Vimy is indelibly linked with Canada because of the battle that took place there in April 1917. The Canadian memorial appears in every history book and travel guide and is one of the main monuments in the region. In fact, Vimy is technically not even part of France, as the monument officially stands on Canadian soil. The Moroccan monument was in fact res- tored a few years ago (paid for by the King of Morocco), yet passes (almost) unnoticed. So why is it here? The reason for its presence is quite easy to identify: fortified and held by the Germans since 1914, Vimy Ridge had long been coveted by France because of its stra- tegic position, in the same way as the hill of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. In 1915, the French and German armies confronted each other in the Souchez sector, each embedded in successive lines of trenches. Despite its weak artillery, France’s continued aim was to retake Lorette and to break through the front. On this occasion it set Vimy Ridge as its objective, even though this seemed somewhat unrealistic at the time. On Vimy Ridge On 9 May, the Moroccan Division went directly on the attack, and against all the odds it broke through four successive lines of German trenches to reach the ridge an hour and a half later. Even though its losses were heavy, its success was undeniable, incredible even. So incredible, in fact, that the reinfor- cements which should have been following to clean up the sector, were not there...or even ready, and were too far away to react quickly. As a result, it was a question of holding the position to the death. Pierre Miquel wrote in La ButteSanglante(TheBloodyHill):“Thetroops of the Moroccan Division made a mistake in winning the battle, as it then became a question of minimising their achievement […] given that the resources to back up what had been achieved were not in place”. A sacrificed division The Moroccan Division was then considered a target for enemy fire… which is another way of saying that it was sacrificed, hence the reason for the Moroccan Division’s com- memoration at the memorial. However, in the eyes of the sociologist Abdelmoula Souidia (Memoria Nord association): “this is not true”, in the sense that it gives the impression that it honours the memory of Moroccan soldiers whereas, in fact, there were no Moroccans in the Moroccan Division. The Division was given its name because it had returned from Morocco in August 1914. Subsequently reorganised, it comprised units of varying origin. In the case of the assault on Vimy Ridge, its troops were made up of Algerian soldiers, recruited in Algeria or Tunisia, as well as legionnaires, and forei- gners of every description ranging from American, Polish and Czechs to Swedish and Swiss volunteers, including the writer Blaise Cendrars. Where are the Moroccans? Given the circumstances it’s not easy to work this out. What is clear, however, is that Moroccan soldiers were engaged on the Artois front. The presence of the 1st Moroccan Infantry regiment is highlighted in May-June 1915 around Angres and Aix-Noulette. We also know that infantry regiments of Moroccan Spahis were in action in Arras and Hesdin. Abdelmoula Souidia himself talks of the caïdmia (lieutenant) Brick Ben Kaddour, one of the few Moroccan officers who took part in the defence of Béthune and was killed at Radinghem-en-Weppes, and of one of his friends, Abbas Ben M’Hamed, killed at Richebourg in 1914. However, without an in-depth knowledge of regimental history, it is particularly difficult trying to find detailed information as there are no Moroccan, Algerian or Tunisian cemeteries – only the Muslim cemeteries in Lorette, and in La Targette, where Muslim tombs from 1939-45 are more numerous than those from 1914-18. Hence the question: what happened to the Moroccans who died? The answer can be found in various cemeteries of the region, and is directly linked to the composition of the different army corps. It’s worth noting that more than 30,000 Moroccan soldiers (37,000 according to Pierre Miquel) left their home country to fight along- side French troops. W orking with the Memoria Nord association, sociologist Abdelmoula Souidia regularly brings school pupils to the region’s military cemeteries and memorials. “These places are full of meaning” he says. The history which these pupils learn in class is also their history. “They are a part of the history of France”. These visits take them away from the world of the working class, which has been their only reference point until now. “Their parents came here to work, and now all of a sudden they are heroes”, continues Abdelmoula Souidia, whose father was a miner at Évin-Malmaison, a job which commands a huge amount of respect. The sociologist explains that Morocco was a protectorate (unlike Algeria, which was a colony) and that Moroccans came to fight in France because their king asked them to do so. There was a huge response to his appeal. Moroccans came to France with their horses; they had long hair and their traditional djel- laba robes flapped in the wind as they galloped across the fields. They were disliked by the Germans, who nicknamed them the Swallows of Death. Today,asignificantnumberofMoroccanshave ancestors who fought in France. This is a part of their history. Abdelmoula Souidia explains that he is often questioned by Moroccans who want to know where a particular tomb is situated. Not an easy question to answer, as there are so many unknown soldiers in the tombs. And even once they’ve located the tomb, they are not always likely to obtain a visa to visit France. Much remains to be done for attitudes to change in this respect. Formalities can also take a long time to be completed. This was certainly true in the case of Brick Ben Kaddour, a Muslim who had been erroneously buried under a Latin cross. Captain Josse, a former Spahi, discovered the mistake and became involved in lengthy nego- tiations in order for the soldier to be laid to rest under a Muslim stele. It’s clear that conside- rable work still needs to be done to comme- morate sacrifices made. Mr Souidia, who is looking for financial backing for a book on the subject, reminds us that “Moroccans helped to build the French Empire”. In other words, they contributed to the country’s greatness. After the end of the war, these men returned to their own country with a completely different image of France. As far as the Algerians are concerned, the historian Carl Pépin explains that the First World War helped to build their awareness of themselves as a people who aspired to inde- pendence. These feelings were reinforced by the Second World War. For the Moroccans, who had a much older history as a nation, such reinfor- cement was not needed. Nonetheless, this war undoubtedlystrengthenedtheirdesiretoreject their status of a protectorate, which was dis- liked by many. For French citizens of Moroccan origin, considerable work still needs to be done to commemorate sacrifices made. A ceremony in the Muslim section of Lorette cemetery. PhotoMemoriaNord Photo:AlainJacquesdocumentarycollection They are part of the history of France Thanks to their glorious ancestors who came to fight alongside French soldiers They are part of the history of France The “café” in a Moroccan camp near Aix-Noulette The memorial to the Moroccan Division Photo:AlainJacvquesdocumentarycollection Photo:PhilippeVincent-Chaissac From Africa to the Artois, Algerian infantrymen, in Carency

- 6. 6 Text : Marie-Pierre Griffon Numerous accounts tell of acts of both remarkable and more modest female bravery. “Women made the Resistance what it was”, explains 88-year-old Henri Claverie, a historian from Hénin-Beaumont. “They broke through enemy lines to pass on messages; they lived in caves, only venturing out to visit the supply depot in order to feed their families; and for hours on end they would grind flour in coffee mills.” Simone Caffard, whose story was uncovered by Raymond Sulliger from the Cercle Historique de Fouquières-lès- Lens, was in her own way a young heroine. A gifted teacher who was passionate about education, she gave lessons to children in the most trying circumstances and worked tirelessly to ensure that they passed their “certificat d’études” exams in 1916. Sadly, she fell ill the following year and died. It’s a lesser-known fact that women were victims of abuse and violence (which included rape, forced labour, deportation and savage repression) if they were found to be part of the Resistance movement. The atrocities to which they were subjected have not been recorded by history, largely because the cruelties of the Second World War have taken their place in the collective memory. As for children, they, too, played their part as best they could. Raymond Sulliger has discovered anecdotes in the work by Alfred Crépe, in particular those relating to the children of Fouquières, who would sing under the noses of German soldiers returning from Lorette: “Té peux chirer tes guêtes Té n’mont’ras pas Lorette Té peux chirer tes bottes Té n’mont’ras pas la côte!” (“You can polish your leggings You’ll never take Lorette You can polish your boots You’ll never take the hill!”) He also recounts how the most daring childrenwouldplacebricksinGerman cooking pots when the cook’s back was turned or do their best to stand up to the enemy in their own way. As the Kommandantur had given an order that all men and young people should greet officers by removing their cap, some walked around bare-headed, which was far from common at the time! Emancipation Few studies have been carried out on the lot of civilians in the occupied zone, although numerous eye-witness accounts tell of difficult living conditions. Requisitions, collective atrocities, reprisals and forced labour became increasingly common. From 1914 onwards, civilians were a workforce which could be exploited for “the war effort”, in particular for the reconstruction of infrastructure destroyed as a result of the fighting. When they resisted, civilians (and occasionally even women and young girls) were deported to forced labour camps, where they formed ZABs (“Zivilarbeiter- Bataillone” or battalions of civil workers) and wore a distinctive emblem: a red armband (brassard rouge), which some wore until 1918. Living conditions for these “Brassards Rouges” was similar to those of prisoners in deportation camps. A rebellious citizen Georges Cambier refused to submit himself to the will of the Germans and was punished as a result. Along with five hundred or so other civilians, he was taken - “like a convict” in the words of his granddaughter – to where labour was needed, mainly in the area around Vadancourt (in the Aisne département). At the railway station he witnessed civilians being hit with the butt of rifles, bitten by dogs and summarily executed. Upon arrival, hunger and ill- treatment were the norm. “We washed using the morning coffee, and once that was done we had to drink it as we were so short of water”. Those who still refused to work were locked in flooded cellars and sheds full of foul-smelling manure. Every three days they received a litre of soup without bread. After three weeks many broke down… Others were enclosed in crates and some went mad. The hospital was, unsurprisingly, like an abattoir and the dead could be counted in their hundreds. Censure Personal correspondence was authorised but had to be written with a pencil to avoid censure. Miraculously, an injury to his shoulder enabled Georges to return home, “but he had to leave for fear of reprisals against his family.” He was finally able to put this hellish existence behind him in 1917. In the north, he saw his mother once again, who was mourning the death of his father. After the war he played his part in the reconstruction of local mines and put his talents as a woodworker to good use for the Compagnie des Mines de Béthune. Nowadays, not a single monument pays homage to the “Brassards Rouges”. “Their resistance has been largely ignored”, regrets Philippe Égu. “However, they served their country well!” The Brassards Rouges, resistors to the occupation. Photos: Philippe Égu collection the forgotten men of history The “Brassards Rouges”: Photo:PhilippeÉgucollection Women and children first Rens. http://pabqt.free.fr/mairie1/vieclav.html http://fouquiereschf.free.fr/ Simon e Caffard died in January 1917Photo:CercleHistoriquedeFouquières-lès-Lenscollection Photo:CercleHistoriquedeFouquières-lès-Lenscollection FRENCH H AVE you heard of the “Brassards Rouges”? Philippe Égu from Grenay has shown a special interest in the forgotten ranks of civilian workers who, refusing to work for the enemy, were deported, mistreated and tortured. This was the case for his maternal grandfather, Georges Cambier, a joiner, who was taken away by force at the age of 19, and who survived deprivation and numerous beatings. Fouquières-lès-Lens. Occupying forces posing with local inhabitants - in this instance, the Musin family - as they would in a hunting scene. The “Brassards Rouges”: the forgotten men of history It is often said that the First World War played a significant role in the emancipation of women. However, this is questioned by his- torians, who claim that the changes which took place at this time were fairly superficial. If changes did take place, they did not last long; once the war was over, women soon found themselves back in the home. Those who gained the most were probably educated or middle-class women. A “baccalauréat feminin” was introduced in 1919, followed by the introduction of equal pay for teachers. All women, however, benefited from the fact that clothes became simpler, as corsets, cumbersome long dresses and uncomfortable large hats were all abandoned. This marked the beginning of the liberalisation of women’s bodies...

- 7. 7Text : Marie-Pierre Griffon Émilienne Moreau and her family left Wingles for Loos-en-Gohelle in June 1914. Her father, a retired mine foreman, was appointed the manager of a small shop on the main square of this large mining town. Émilienne, who had just turned sixteen, was destined for a career as a teacher. The alarming news of the final days of July worried her a little but “a young girl pays little attention to news relating to foreign politics; and to tell the truth I had little idea about the Serbia that was being talked about...”, she wrote in “Mes mémoires, 1914-1915”, which appeared in the magazine Le Miroir. When, at 4pm on 1 August, the siren brought miners up from the pit and the alarm sounded in local mining villages, the reality soon hit home. After mobilisation and the departure of her brother for the front, days of uncertainty were followed by days of anguish, and after the long processions of eva- cuated civilians came the arrival of the German occupying forces. Time passed. Gradually, with each new horror and act of pillage by the Uhlans, the young girl’s indignation and confidence grew. Acts of fortitude Émilienne created a special obser- vation post in her attic, watching events through her binoculars. She started to observe the Germans digging shelters in the slag heap, installing themselves in the sorting buildings and, on 8 October 1914, setting up machine guns between the pylons of La Fosse. “A moment later, we spotted our soldiers on the hill. I suddenly started shouting: the poor souls are going to be mown down by the machine guns…” Without thinking, the young girl started to run “like a mad woman” between the bullets and pieces of shrapnel to warn the soldiers. French shells rained down on the Germans. “Thank you my child, you’re a very brave girl!”, the ser- geant said to her. “You did well!”, her father whispered as he hugged her. The young girl’s resolve har- dened with every passing day. When the town hall was in flames, she ran to put out the fire and save the public archives; when the Germans threatened her, she held her head up high, brandishing a bottle at them. “(...) I asked myself whether it was really me who had behaved with such fortitude,” she wrote later. « Give me two grenades » When wounded British soldiers passed through Loos-en-Gohelle, Émilienne Moreau, who was devas- tated by the sight, became a first-aid worker. With her mother, she trans- formed the family home into an infir- mary and provided useful assistance to a British doctor who established a clinic there. In the book “Petits héros de la Grande Guerre” (Unsung Heroes of the Great War), Jacquin and Fabre told how the wounded continued to arrive in great numbers and that many of them remained outside on the street des- pitetheirseriousinjuries.“Ignoring the pleas of the major who feared for her life, she left the safety of her house and off she went amid the crackle of gunfire to give water to those in need, remo- ving the wounded from among the dead…” When she suddenly saw three Germans head towards an injured Scottish soldier, she decided toattackthemaccompaniedbythree other wounded soldiers “who could barely stand up”. “Follow me”, Émilienne Moreau whis- pered, “I’ll go first.” However, a noise had undoubtedly revealed their presence and a German b u l l e t s k i m m e d past the young girl’s hair. She decided that all was not lost. “Stay here”, she said, showing the British soldiers the door to the cellar, “and give me two gre- nades.” On another occa- sion, a further act of bravery was to immortalise Émilienne Moreau in the hearts of the inhabitants of Loos-en-Gohelle. On her own, with a wounded soldier on a stret- cher, she saw two Germans in front of her pointing their guns directly at her. Their shots missed but the young girl’s did not. “The young girl then spotted a revolver (...). Émilienne grabbed hold of it. Feverishly, she fired shot after shot at random (...), and the Germans, shot at almost point- blank range, fell one after the other.” Frédo Duparcq, from the “Loos- en-Gohelle sur les traces de la Grande Guerre” association, knows Émilienne’s story off by heart, or at least the one recounted to him by the village’s older residents, as recollec- tions vary somewhat between Les Mémoires d’Émilienne, the book by Jacquin and Fabre, and the memo- ries of local inhabitants. Whatever the exact story, Émilienne Moreau’s actions are to be applauded, and Frédo, who has carefully read through the rare edition of Le Miroir, is happy to share the details of this adventure. The story has a happy ending, with medals and decora- tions galore: “On the day that Émiliennewasaccompanyingher sister to Béthune for an opera- tion, the latter injured by a shell, a car stopped alongside them. A few moments later, she was presented to the British general in command of the sector, who wanted to thank her and inform her that he had advised both the French and British governments of her actions. On 27 November 1915, following a mention in dispatches by General Foch, General De Sailly presented the Military Cross with palm to the young heroine. On the recom- mendation of General Douglas Haig, the British ambassador in Paris also awarded her, in the name of His Majesty the King, the Military Medal, the Royal Red Cross First Class and the Medal of the Order of St John of Jerusalem.” It goes without saying that the Germans would have good reason to remember the name of É m i l i e n n e Moreau when they returned to the region twenty years later. Émilienne showed the same passionate commit- ment in the Second World War as she did in the first, and the woman known as Jeanne Poirier or “Émilienne la Blonde” in the heart of the R e s i s t a n c e would be talked about for many years to come. A young heroine… T o say that the inhabitants of Loos and the “Loos-en-Gohelle sur les traces de la Grande Guerre” association are proud of their heroine Émilienne Moreau is something of an understatement, as it is worth stating from the outset that in the Pas-de-Calais fearless 16-year-old girls with a grenade in one hand and a revolver in the other were few and far between! In turn a loving daughter, teacher, nurse and a combatant, she never once submitted to the enemy or lost her nerve. Émilienne Moreau from Loos-en-Gohelle The war was far from over yet the young Emilienne Moreau had already been decorated with the Croix de Guerre with palm, which she received on 27 November 1915 from the French President, Raymond Poincaré, at the Elysée Palace. She would also be the only woman to be awarded the Military Medal, a British distinction, and went on to receive the Royal Red Cross, the Medal of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem and the Légion d’Honneur. Photo:“Loos-en-GohellesurlestracesdelaGrandeGuerre”associationcollection. Photo:HuguesChevalierprivatecollection

- 8. 8 Text : Marie-Pierre Griffon Vera Brittain was born in 1893 into a wealthy English family. From an early age she refused to accept the res- trictions placed on young women of the time, and envied her younger brother who was able to leave the family home without getting married. A rebel by nature, she talked of nothing else except her independence, her stu- dies and her career. Despite the disapproval of her father, she succeeded in gaining a place at Somerville College, Oxford, where she fell in love with Roland Leighton, a friend of her brother. The future seemed nothing but rosy for them when war broke out in 1914. “Carried away with emotion and the glorious face of patriotism” (these were her words),Vera put her name forward as a volunteer and underwent training as an auxiliary nurse, once again against the wishes of her father. It was only three weeks later that she began to truly understand the meaning of war, and every day she was more and more horrified by the but- chery of it all. In England, Malta, France and Étaples in particular, she learnt of the deaths of her friends, her fiancé, and later on, her bro- ther. She found herself in the absurd position of working relentlessly to save lives, in particular those of German prisoners, at the same time as her brother was trying to destroy them! It was at this time that her pacifism took root. She wrote and published her war diary from 1913 to 1917, entitled “Chronicle of Youth”, as well her “Testament of Youth 1933”, an autobiography in which, she says, she appealed more to the mind than the heart. The story has been screened in England in a very popular TV series. Vera Brittain became tirelessly involved in the paci- fist campaign during the inter-war years, and later campaigned for nuclear disarmament, the independence of the colonies, and the anti-apar- theid movement in South Africa. ENGLISH Vera Brittain was a nurse in Etaples. Her involvement in the Great War made her name as a militant and internationally famous pacifist. The camp at Étaples A huge camp was therefore set up to store equipment, to pro- vide training for troops and to ensure their fitness. It also housed around twenty hospitals, with 20,000 beds, to receive full trainloads of wounded sol- diers arriving here. It even became necessary to build an additional station. The injured were first received at rest posts before being taken to the camp in ambulances by British army auxiliaries known as the “Khaki Girls”, who were quickly given the nickname of “Cats qui gueulent” (screaming cats) by locals in Étaples. These young women, who also fulfilled the role of cooks, typists, telepho- nists for military staff etc, “eli- cited not even the slightest astonishment from local inha- bitants who, for the first time in their lives, were seeing women dressed in uniform”, explains Pierre Baudelicque, a history professor at the uni- versity. Upon their arrival, in Étaples as elsewhere in the Pas- de-Calais region, the soldiers received a warm welcome from the local population, “who saw them as allies determined to support the French fight, even if in reality Great Britain had declared war to protest against the German violation of Belgian neutrality”, adds Xavier Boniface, a lecturer at the Université du Littoral. Illegitimate babies On occasion, romances deve- loped between soldiers and local women. There were marriages, very few in fact (the figure of just five is mentioned), perhaps because of the differences in reli- gion (the soldiers were Anglican, the local women Catholic). These “fraternisations” resulted in several illegitimate births in every social category of the population. “Babies born from these day- or month-long liai- sons were of course subjected to gibes which the cocky and ever-alert locals of Étaples never missed an opportunity to make up,” wrote Pierre Baudelicque in his famous work “Histoire d’Étaples. Des ori- gines à nos jours”. These poor children were picked upon and often subjected to insults: “Va donc, espèce ed’monster ed’batard d’inglé!” (Clear off you little monster and bastard of an Englishman) The “Black Plague” Prostitution clearly prospered and with it the “Black Plague”, namely venereal diseases. This curse was not immediately noticed due to the attention given solely to the war-wounded. In France, the big cities and most of the country’s s e c o n - d a r y t o w n s became sources of contagion. In Étaples, a hospital was enti- rely set aside for soldiers who had contracted these “special” illnesses. The epidemic also spread within the civilian popu- lation and is one of the reason why the Franco-British cohabi- tation became a little less har- monious over time. In addition to venereal diseases and pros- titution, other problems which tend to develop wherever there are soldiers manifested them- selves: the sale of alcohol, fights, an increase in crime etc, even though in Étaples the soldiers rarely left their camp. Furthermore, the population was unhappy that its rights were being restricted, particularly in terms of movement (passes, ceasefires etc). Relations were stretched even further when, on the occa- sion of the mutiny at the end of 1917, the soldiers left their camp furious with rage, as a result of which local “Étaplois” were sub- jected to a week of hell… which is still talked about even to this day. Vera BrittainVera Brittain A volunteer turned spirited pacifist Local women and children...and English soldiers. FraternisationFraternization Photo:PierreBaudelicquecollection É TAPLES was a remarkable railway crossroads, as it was from here that the battlefields of the Somme and Artois could be reached. If you take into account the proximity of Boulogne-sur-Mer and the existence of extensive available land, you can easily understand why the British were so keen to establish themselves in this perfect strategic location. It was here that the military had extended the largest British base in France. In all probability, over a million men passed through here between March 1915 and November 1918, and the base accommodated 60-80,000 soldiers at any one time. Photo:PierreBaudelicquecollection

- 9. 9Text : Philippe Vincent-Chaissac BRITISH cemeteries are dotted around the Pas-de-Calais, with most of them located on the Artois front. The largest ceme- tery is situated in Étaples, far from the trenches. The expla- nation is simple: Étaples was the base camp for the British, who had established several hospitals on the hill (nowadays occupied by buildings) overloo- king the old town. “Étaples is the most painful of all the cemeteries. It is here that men killed slowly by gangrene and gas, blind and with their lungs destroyed, are laid to rest. They were buried ten, fifteen, twenty at a time”. In total there are 11,658 graves here, 800 of which fol- lowed the German bombardment in 1918. The Bull Ring What we do know is that this cemetery situated above the Canche river, on the road to Boulogne, stood alongside a trai- ning ground, the Bull Ring, in the military camp at Étaples, a compulsory stopping-point for all those who, having disembarked at Boulogne, required training before being sent to the fronts in the Artois and Flanders. It was a veritable hell where men were subjected to extreme discipline and very hard training, and from where they left, with few regrets, for the front. This was, in short, psychological preparation which could have been justified had it not been so excessive that it led to a huge mutiny in September 1917 – a mutiny which Great Britain covered up with a veil of silence. A six-day revolt Even historians, who were aware of the facts from accounts gathered from the local popu- lation, were unable to get to the very bottom of a story that the vast majority of English, and more widely the British, ignored until 1978, the year a book by William Allison and John Fairley, entitled The Monocled Mutineer, was published. In the view of the his- tory professor Pierre Baudelicque, this work needs to be read with a hint of caution. It was criticised in England, although it had the benefit of forcing an admission that this revolt, which lasted six days, actually took place. It was a controversy at the time, is still a controversy today, and will remain so until 2017, the year in which the cloak of secrecy relating to military archives can be lifted. For all that, the historian from Étaples confirms the majority of the views put forward in this book translated by Claudine Lesage in 1990, including the fact that a very large number of soldiers deserted to live in the woods, marshland and dunes surrounding the camp, as well as in the tun- nels and caves dug in the chalky landscapes around Camiers. Among these deserters was a cer- tain Percy Toplis, to whom Allison and Fairley attributed an impor- tant role in the sequence of events. According to Pierre Baudelicque, this man was certainly among the deserters and was one of the agitators, but we should attach a little less importance to his role and actions. It appears that the revolt was partly triggered by a tragedy: the killing (by accidental gunshot according to the official report) of Corporal Wood, who was sur- prised by a military policeman while in conversation with a young woman from Aberdeen wearing a WAAC (Women's Auxiliary Army Corps) uniform – a liaison which was strictly forbidden. This was the straw that broke the camel’s back for the soldiers of the camp, who had had enough of the treatment metered out to them by Brigadier General Thomson, the camp commander – described as a model of brutality and tyranny – as well as by military instruc- tors and police. The entire camp was overcome by anger at the kil- ling, which resulted in 3-4,000 soldiers, mainly from Scotland, Australia and New Zealand, stor- ming through the doors and fences surrounding their billets. Their uncontrollable fury was targeted at their “torturers”, as well as at French civilians, nurses etc, and resulted in repeated beatings and rapes. Pierre Baudelicque highlights the recollections of Lucien Roussel, who was 15 years old at the time, and who witnessed the British troops “attack the town like real savages, pillaging and destroying everything before them”. A mutiny waiting to happen At the beginning, Brigadier General Thomson had wanted to convince people that this was just a fit of anger. However, it was much more serious than that given that it lasted for six days. Alongside the brutalities endured by the soldiers, and the death of Corporal Wood, other factors almost certainly contributed to this mutiny which had been sim- mering for some time. The ques- tions that need asking are nume- rous. What information did the soldiers have in their possession? Did they know that there was also talk of mutinies on the French side? What influence was exerted by the deserters who were acting as camp guards and who joined the troops? Had pacifist and com- munist propaganda infiltrated the camp? Mutineers killed in combat The opening-up of the archives will perhaps shed new light on this affair which ended on Friday 14 September, the date on which calm was considered to have returned. This was made possible by the arrival of troops whose role was to restore order, including Bengal Lancers who only required a single order to open fire. Faced with this impressive demons- tration of force, the mutineers returned to their ranks and were soon moved to the Flanders front where General Haig was readying himself to launch the deadly offensive at Passchendaele. Most of the mutineers were killed there without having had the opportu- nity to explain exactly what hap- pened in Étaples, where a com- mission of enquiry identified the ring-leaders.“It is thought that a dozen or so executions took place”, Pierre Baudelicque wrote in his Histoire d’Étaples. Other sentences were also passed. How many men were executed? This is another ques- tion that remains unanswered as the bodies of those shot were taken back to England. Nowadays, all that remains of the Étaples camp is this impressive cemetery. Nothing, of course, to indicate that the power of the British army had wavered here. Allison and Fairley reaffirmed this. Pierre Baudelicque takes a more level-headed approach: “the Étaples mutiny wasn’t the only one. Others had taken place in Le Havre, in Calais… and in Dover”. What is certain, however, is that cen- sorship had worked effectively and that the British silence had done its job. “The older bro- ther of my mother, who was English, remained in Étaples throughout the war, and never spoke of a revolt among his colleagues”, adds Pierre Baudelicque. A mutiny Training in the Bull Ring, the scene of daily bullying and insults. The site was situated alongside the present-day military cemetery. Abuse in the Bull Ring Eye-witness accounts gathered from veterans, fifty or sixty years after the event, are edifying. Troops arriving in Boulogne immediately came under the control of the dreaded Canaries (so-named because of their yellow armbands), who would make them walk all the way to Étaples by forced march, with only a half a slice of bread and a glass of water for sustenance during a brief stop in Neufchâtel – a foretaste of what was in store for them once they arrived in Étaples. Cut off from the world, they were the victims of both moral and physical abuse during their entire training period. This breakdown of mental strength was etched on their faces. The poet Wilfred Owen, who viewed the Étaples camp as “an enclosure where animals are left for several days before the final carnage”, expressed this feeling, speaking of the blind look in the eyes of his fellow men, “expressionless, like a dead rabbit”. The Bull Ring was the scene of every kind of bullying and insult on a daily basis. “I was wounded twice but that was nothing compared with what I went through in Étaples”, wrote one veteran. “To tell the truth, I had experiences in Étaples that were as bad as those at the front”, another added, “but nowhere did I feel such a strong sense of anger”. A sentiment that was even more legitimate given that the instructors who were putting them through so much had never set foot in the trenches themselves. beneath a veil of silence Photo:ClaudineLesagedocumentarycollection

- 10. 10 Text : Christian Defrance “Play for them Laidlaw. For the love of God, play for them!” The piper plays Blue Bonnets O’er the Border then On the Braes O’Mar. Despite being hit twice in the leg, he continues to advance. When his comrades have achieved their target, he returns to the trench with his bagpipes. Piper Laidlaw’s sortie is one of the more unusual epi- sodes of the Great War. Having returned home alive from the conflict, Daniel Laidlaw played himself in the film “The Guns of Loos” in 1928, also appearing five years later in “Forgotten Men”. “On 25 September 1915, my hair turned white in just a few hours”, explained Daniel Laidlaw, who died in 1950. The piper of the 7th Battalion King’s Own Scottish Borderers symbo- lises “to a T” the Scottish pres- ence in the British army – a pres- ence that hardly passed unnoticed given that Scottish soldiers wore their own uniform: a kilt, of course, along with a leather sporran, and a beret on their heads. These sol- diers made a real impression, so much so that the Germans referred to them as “Damen von Hölle”, the women from hell; the local population was astonished to come across them without any unde- rwear! The “women from hell” was perhaps an apt term as cou- rage and commitment epitomised the Scottish units in every battle they were involved in. Close to 150,000 Scots died during the First World War, which represents 20% of British losses. To get an idea of the slaughter, a comparison needs to be made with Australia. Australia and Scotland each had a population of five million in 1914: 60,000 Australians died in 1914-18 com- pared with 147,000 Scots. The losses were huge during the Battle of Loos: 50% of the men in each of the eight battalions of the 15th Scottish Division who attacked the village and Hill 70. U NIONISTS and Nationalists. Protestants and Catholics. North and South. An island divided, even more so after the bloody events of the 1916 “Easter Rising” in Dublin (the rebellion against the British occupation and the terrible repression that followed). However, a similar hell existed in the trenches for the 210,000 Irish who served in the British army during the First World War, in which 35,000 of them lost their lives. Yet, it wasn’t until 1998 that, as a sign of reconciliation, the “Island of Ireland Peace Park” was inaugurated in Messines. Having arrived in France at Le Havre from 18 December 1915 onwards, the16th Irish Division had their first taste of the trenches in early 1916. From 27 to 29 April, it was fully engaged in the Battle of Hulluch, one of the battles of the Great War in which poisoned gas was used. During the German attack on 27 April, out of the 1,980 victims, 570 died, to be followed by numerous wounded later on as a result of respiratory problems. To incite the Irish, the Germans had placed posters in front of the trenches recalling the events of the “Easter Rising” on 24 April. In August 1916, the 16th Division adopted new positions in the Somme. In June 1917, the Catholics from this 16th Division joined up with the Protestants from the 36th Ulster Division near Messines, taking the village of Wijtschate side-by-side on 7 June. Following action at Péronne and Hamel, the 16th Division was relieved in early April 1918, following an order for it to return to England via Aire-sur-la-Lys and Samer. 2 5 SEPTEMBER 1915, the Battle of Loos. The deafening sound of bombs, bullets whistling through the air, and cries of pain and terror. Suddenly, a traditional Scottish sound seems to drown out the hail of bullets. Piper Daniel Laidlaw has climbed out of the trenches with his bagpipes to accompany his comrades towards the German lines. 23 August 1918 : the 2nd Battalion the Royal Scots attacks the Germans entrenched in Courcelles-le-Comte from the rear. The soldier Hugh McIver, a company runner, heads off alone to attack an enemy posi- tion. He kills six Germans, captures twenty more, and seizes two machine guns. When a British tank homes in on the wrong target, aiming at its own side, McIver climbs on to the vehicle and re-adjusts the shot – heroic acts which earned him the Victoria Cross, awarded posthumously to his parents in 1919 as Hugh McIver was killed on 2 September near the Bois de Vraucourt. He was 28 years old. During the Great War, the Valenciennes artist Lucien Jonas (1880- 1947) painted more than 2,000 sketches and portraits of Allied officers and soldiers, publishing a total of fifteen albums. Photo: “Three Scottish soldiers” (Hugues Chevalier private collection) 23 August 2008 : following consi- derable research, and as a result of the perseverance of Christophe Guéant, a keen local historian who for two years had received the support of The Somme Remembrance Association, Courcelles-le-Comte welcomed men from the 1st Battalion the Royal Regiment of Scotland and forty or so members of Hugh McIver’s family, who had come to attend the inauguration of a “Franco-English-Scottish” memorial to honour the memory of this Scottish soldier, Hugh McIver (born in Linwood, Paisley), but also to “salute the sacrifice made by a generation for freedom”. Scots, bagpipes, kilts and courage Blue Bonnets O’er the BorderBlue Bonnets O’er the Border Posters proliferated to encourage the Irish both emi- grants and those who had remained in the country to rejoin English, Canadian and Australian regiments etc. Irish, “united” in the trenches O’Leary, an Irish hero, was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions at Cuinchy from the north and south

- 11. 11Text : Christian Defrance In August 1914, a few days after the German attack on Belgium, 43 young Americans started their training with the famous Foreign Legion. Their motivation? Quite simply, their love of France, and the defence of their beloved freedom... plus, of course, a taste for adven- ture! These Americans, the majo- rity of whom were either intellec- tuals, students or artists (such as the poets Alan Seeger and Henry Farnsworth), found themselves alongside Spanish, Greek and Swiss (including the writer Blaise Cendrars) volunteers. Why the Foreign Legion? This was the only option that would ensure that they kept their American citizenship, given that the United States was not yet at war with the German Empire. These volunteers would see action in some of the bloodiest battles of the Great War, including the French offensive which began on 9 May 1915 (Neuville-Saint- Vaast, Carency, La Targette, Les Ouvrages Blancs) and culminated in the capture of the Notre-Dame- de-Lorette hill. The Rockwell brothers Asheville, North Carolina, in a valley in the Appalachian moun- tains. War is declared in Europe. The Rockwell brothers, Paul and Kiffin,buoyedbyaspiritof“liberty, equality and fraternity”, write to the French consul general in New Orleans in order for them “to pay their share of the debt to Lafayette and Rochambeau”. They didn’t wait for the reply which was a long time coming and took the first available ship, to Liverpool, on 3 August 1914. From here they travelled to Le Havre and Paris, and quickly on to the French Legion on 30 August. Training followed in Rouen, Toulouse and the Mailly camp, before they were “plunged” into the trenches. Wounded at the Chemin des Dames, Paul left active service and became the war cor- respondent for the Chicago Daily News. In 1925, he fought in the Rif War and served in the American army during the Second World War. Born in 1892, Kiffin was wounded for the first time in December 1914. Having recovered from his injuries, he joined up with the Moroccan Division and was wounded a second time, this time in the leg, during the charge on La Targette on 9 May 1915. Six weeks of convalescence followed. Kiffin was transferred to air duties and, along with his compatriots Thaw, Cowdin, McDonnell, Prince, Hall and others, he became part of the famous “Lafayette squadron”. On 18 May 1916, he shot down his first German plane over Alsace. Kiffin Rockwell was to become “the king of the skies” as a result of his 141 successful combat missions, which earned him the Military Medal and the Croix de Guerre. On 23 September, he was killed by an explosive bullet during an aerial duel near the place where he enjoyed his first victory. In a letter to his brother, Kiffin wrote: “If France should lose, I feel that I should no longer want to live”. From Loos to the Bounty An adventurer, soldier, fighter pilot and writer who lived in Iowa, London, Loos-en-Gohelle and Tahiti: this is the incredible life story of James Norman Hall, born in Colfax, Iowa, in 1887. In August 1914, he found himself in London, where he passed himself off as a Canadian in order to enlist as one of Lord Kitchener’s very first volunteers. In September 1915, he took part in the Battle of Loos, where his company was decimated. Whilst on leave, it was discovered that Hall was American, which resulted in his demo- bilisation. This sol- dier-author was quick to relate his terrible experiences in a book, “Kitchener’s Mob”. He returned to France as part of the Lafayette squadron and covered himself with glory as a captain in the U.S. Air Force, receiving the Légion d’Honneur. In 1920, James Norman Hall and his friend Charles Nordhoff left for Tahiti, embarking on one of the most famous collaborations in American literature as the authors of the “Mutiny on the Bounty” trilogy. Weeks mother and son Kenneth Weeks was born in Chestnut Hill, a suburb of Boston, on 30 December 1889. He was edu- cated at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology then the Beaux-Arts in Paris, and planned to make a career in architecture. Kenneth loved writing, Paris and France; on 21 August 1914, he enlisted in the Foreign Legion, spending the winter of 1914 in the trenches. On 17 June 1915, the American was reported missing near Souchez, and his body was recovered on 25 November and buried in the cemetery in Écoivres, near Mont-Saint-Éloi. His mother, Alice Standish Weeks, lived in Paris from 1915 onwards, providing a lodging in her home for volunteers on leave, and writing to them on a very regular basis. Some of this correspondence from “Maman Légionnaire” (Mother of the Legion”), as she was affectionately known,wassubsequentlypublished. From Massachusetts Far from the somewhat romantic image of the “American colony in Paris”, many U.S. citizens signed up with British or Canadian regi- ments prior to 1917, often using a pseudonym and recruited via Canadian and British missions. This is how, for example, W. Chadwick from the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, killed in action on 15 September 1918, came to be buried in the Five Points Cemetery in Léchelle. He was just 15 years old. Fifteen! Research has unco- vered the identity of this “teenage soldier”, who was William Hesford, born in Massachusetts, and wit- hout doubt the youngest American soldier to die in the Great War. Several hundred soldiers from Massachusetts have also been iden- tified. Metcalf from Maine In August 1914, the mother of 20-year-old William Metcalf learnt that he had left Waite, in Maine, and crossed the nearby Canadian border in order to enlist in the army. She immediately contacted the authorities for them “to return her son”. Upon disembarking in England, William was called by the American ambassador. Are you the young man whose mother is waiting for you at home in Maine? “I’m not that man”, William replied. “I’m from New Brunswick!” – a sta- tement confirmed by his colonel. The ambassador was powerless to do anything. Four years later, on 2 September 1918, William Henry Metcalf, one of the heroes of the Battle of the Drocourt-Quéant Line, was awarded the presti- gious Victoria Cross. Following the Armistice, he returned to his native Maine, where he embarked on a career as a mechanic. He died in South Portland on 8 August 1968. Americans, from La Fayette to Lorette L ONG LIVE America! On 13 June 1917, around two hundred American soldiers and civilians disembarked in Boulogne- sur-Mer. At their head was General Pershing, commander-in- chief of the American Expeditionary Force. America was ready to “finish the job in Europe”, and its participation in the Great War would be one of the keys to the Allied victory. On 11 November 1918, a total of two million “Doughboys” or “Sammies” – nicknames for soldiers from the U.S.A. – were in France, a million of whom had already seen combat; and Foch, Pétain and Pershing already had plans for the involvement of four and a half million men in 1919. By the end of the war, more than 100,000 Americans had lost their lives, and 200,000 had been wounded, in places such as Saint-Mihiel, Château-Thierry, the Argonne, Marne and Meuse. This “official story” has somewhat eclipsed the participation of American volunteers in the conflict well before the U.S.A.’s official entry into the war in the spring of 1917. James Norman Hall, from the Battle of Loos to the Mutiny on the Bounty. Photo: D.R. Kiffin Rockwell, on the left, and fellow legionnaires in the trenches. Photo: www.scuttlebuttsmallchow.com A “Doughboy” with a determined look. Photo: Hugues Chevalier documentary collection

- 12. 12 Text : Christian Defrance “I was aware that villagers had been evacuated, and that the Germans had blown up the church in 1917. My brother had even received a photo of the event sent by a German with whom he corresponded and who had even fought in Sains!” The mayor had even heard talk of the “capture” of the village, of its “reconstruction”, involving the digging of twenty wells, “plus, of course, the British cemeteries”. Except that of the 273 graves at Quarry Wood, 260 are Canadian; of the 257 at the Ontario Cemetery, 142 are Canadian; and of the 227 at the Sains-lès-Marquion British Cemetery, 177 are also Canadian. It was the arrival in Sains of Michel Gravel in 2003 which “set the cat among the pigeons” for the mayor of the village. Since 2001, Gravel, a roof salesman from Cornwall, Ontario, has spent all his time researching Canada’s military past. An inveterate his- tory buff, he has thumbed his nose at academics. In particular, he has published “Tough as Nails” (“Arras à Cambrai par le chemin le plus long”), which pro- vides a new insight into the cap- ture of Canal du Nord. Supporting documentation comes in the form of regimental journals and the recollections of “Hillie” Foley, a roofer from Ottawa. “Gravel told us what happened on 27 September 1918 in Sains-lès- Marquion”, states Guy de Saint- Aubert, “and I wanted to satisfy the curiosity of our local inha- bitants.” No more fighting Hence the inauguration of a com- memorative plaque on the square on 31 August 2008. Ninety years before, on 27 September 1918 to be exact, on the left flank of the Allied offensive against the Hindenburg Line, the 14th Battalion (Royal Montreal Regiment) of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division attacked the Germans who were holding the Canal du Nord. Supported by an artillery barrage and by four tanks from the British Tank Corps, the 14th Battalion established a bridgehead on the fields to the south of Sains-lès-Marquion. After a brief lull, they went on the offensive again, entering the vil- lage from the rear and taking the enemy completely by surprise, with the Canadian “steamroller” taking five hundred prisoners. “A tactical masterpiece within the Battle of the Canal du Nord, the most complex operation of the Great War, and a plan that was incredibly ambitious”, asserts Michel Gravel. “The battle was won here in Sains, so a monument was needed to commemorate it”, he adds, remembering the memorial at the Bois de Bourlon. Although the famous 14th Battalion lost sixty men on 27 September, a total of 9,000 Canadians were killed along the road from Arras to Cambrai between 26 August and 9 October 1918. All these soldiers had made “the supreme sacri- fice”, Michel Gravel pronounces darkly. “He knows them like the back of his hand”, explains the mayor of Sains. “In front of each grave he will tell you that so- and-so died in Marquion, ano- ther at the hospital, and even the names of their parents.” So it was, therefore, at the end of August, that Michel was able to show Jim Vallance “the exact spot where his great-uncle, James Wellington Young, was killed on 27 September 1918”. Jim Vallance, who was making his second visit to Sains-lès- Marquion, is famous in Canada as a songwriter for Bryan Adams, the Scorpions, Joe Cocker, Rod Stewart, Tina Turner and others. Jim Vallance and Bryan Adams wrote “Remembrance Day” (11 November) in 1986: “The guns will be silent on Remembrance Day. We’ll all say a prayer on Remembrance Day”. In Sains- lès-Marquion, everyone is com- mitted to weapons being silenced forever. Liberated in 1918 by the Canadians, the village is now twinned with the German town of Neuenheerse. “There’ll be no more fighting”, sings Bryan Adams. We hope that is the case. H E has counted the graves in three military cemeteries in his local commune. Guy de Saint-Aubert is the mayor of Sains-lès-Marquion and has thrown himself into a commemorative project that he wasn’t in the least bit expecting. He was certainly familiar with the main thread of the turbulent events experienced in his village during the Great War, but there is so much more to the story… From 1914-18 to today: a Canadian battalion passes through Barlin (above); soldiers from the 14th Battalion are buried at the cemetery in Sains-lès-Marquion where Michel Gravel and Jim Vallance pay their respects (below). 1918-2008 619,000 soldiers mobilised Gloriously sunny skies welcomed Queen Elisabeth II to Vimy on 9 April 2007, where she was presiding over the official inauguration of the restored monument. “Victory at Vimy Ridge enabled Canada to occupy an important place in the world, inspiring a young country to become a magnificent nation”, she said. In Canada, everyone knows about Vimy, however in the grand scheme of things this small part of the Pas-de- Calais is just a single episode in Canada’s participation in the Great War. From October 1914 onwards, Canadian volunteers were already arriving in England and were involved in early fighting near Ypres at the beginning of 1915. The Canadian Expeditionary Force had already distinguished itself in the battles of Ypres and in the face of the horrors of poison gas, as well as in Neuve-Chapelle in March 1915, and Festubert and Givenchy in May and June 1915. From July to November 1916, there they are again in the tragic Battle of the Somme. And then at Vimy Ridge from 9 to 14 April 1917; Arleux; the 3rd Battle of the Scarpe; Souchez; Avion; Hill 70 and the offensive against Lens in August 1917 (the only large-scale urban battle in the Great War); Amiens in August 1918; the breaching of the Hindenburg Line during the autumn of 1918; and the advance from Arras to Cambrai. In total, the Canadian Expeditionary Force committed 619,000 men to the First World War (a figure based initially on volunteers and then on conscription after Vimy, to which Quebec was opposed). There were many immigrants in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, and it is estimated that half of all its soldiers were born in the United Kingdom. Add to these Ukrainians, Russians, Scandinavians, Dutch, Belgians and a plethora of Americans, not forgetting four thousand native Indians, Inuits and Métis. The human cost was a very heavy one: 66,655 dead, of whom 19,660 were uni- dentified. In places such as Achicourt, Vimy, Étaples, Écoivres, Thélus, Villers-au-Bois and elsewhere, 28,785 Canadian officers, non-commissioned officers and soldiers are laid to rest in the six hundred or so cemeteries and burial sites in the Pas-de-Calais. from Vimy Ridge to the Canal du Nord Canadians, from Vimy Ridge to the Canal du Nord Photo:ChristianDefrancePhoto:DominiqueFaivredocumentarycollection