Tribal Natural Resources Management 2020 Annual Report

- 1. 2020 Annual Report from the Treaty Indian Tribes in Western Washington Tribal Natural Resources Management

- 2. 2 Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission Member Tribes of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

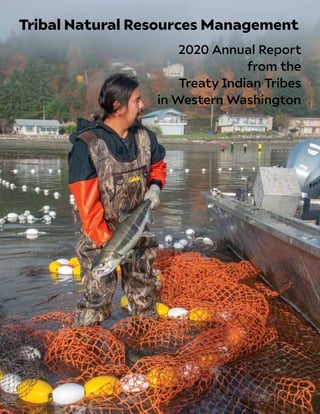

- 3. 32020 Annual Report From the Chair.........4 Harvest Management.........6 Salmon........6 Shellfish........7 Marine Fish.........8 Hatchery Management.........9 Habitat Management.......10 Wildlife Management.......11 Regional Collaboration.......12 Puget Sound Recovery.. ...12 Water Resources.......13 Forest Management.......13 Ocean Resources.......14 NWIFC Activities.......15 Table of ContentsNorthwest Indian Fisheries Commission 360-438-1180 6730 Martin Way East Olympia, WA 98516 contact@nwifc.org nwifc.org nwtreatytribes.org Above: A chinook salmon makes its way upstream toward the Nisqually Tribe’s Clear Creek Hatchery. Chinook returns were decent, though not robust this year, marking one of the few bright spots in salmon returns. Front cover: Skokomish tribal member Pat Johns loads his chum harvest into a tote. Tribal members harvest chum that return to the state’s Hoodsport Hatchery every fall. The chum fishery was cut short after a test fishery conducted by the treaty tribes and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife found lower re- turns than forecast. All tribal and nontribal chum fisheries were closed early in South Sound. Photos: Debbie Preston Map, opposite page: Ron McFarlane

- 4. 4 Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission Every year the treaty tribal and state salmon co-managers’ job of sharing and rebuilding a steadily shrinking re- source becomes more difficult. The biggest challenge is developing fisheries in the face of declining salmon habitat that is being lost and damaged faster than it can be restored. That factor is being further complicated by climate change, the needs of southern resident orcas, and an explosion of seal and sea lion populations. Poor ocean conditions attributed to climate change and the ongoing loss of salmon habitat contributed to general- ly lower salmon returns across western Washington in 2019. Struggling chinook stocks from the Stillaguamish and Nooksack rivers as well as Hood Canal resulted in limited fish- eries in some areas. There also were low returns of coho, chum and pink salmon throughout the region. The needs of southern resident orcas also must be factored into the co-manag- ers’ salmon season decision-making. Like the chinook salmon they depend on, their population continues to steadily decline. California sea lion and harbor seal populations in western Washington have exploded in recent years. The co-manag- ers agree that we must gather data on the populations, diets and ecological impacts of seals and sea lions to ensure that their management supports recovery efforts for salmon and southern resident orcas. As the job of managing salmon is more difficult every year, each management decision that the tribes and state make as co-managers requires increasingly careful consideration and closer coordination. A strong step in that direction came with the appointment of Kelly Susewind as director of the Washington Depart- ment of Fish and Wildlife. Although new to the world of salmon management, he provided strong leadership during the North of Falcon process to help the tribes and state meet our shared conservation challenges. Unfortunately, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) effort to roll back Washington’s water quality stan- dards picked up momentum in 2019 and may conclude in early 2020 despite strong opposition from the tribes, state govern- ment, environmental groups and others. Meanwhile, work on implementation of the culvert case continued in 2019 but tribes are concerned the state may be shortchanging efforts to meet the fed- eral court’s mandate upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court. Water Quality Standards The EPA continued its crusade to roll back Washington’s water quality stan- dards – the most protective in the nation – based on an industry trade group petition claiming the rules will increase their cost of doing business. The federal agency decided to roll back the existing Human Health Criteria without consulting the tribes or the state, despite the federal government’s trust obligation to hold government-to-govern- ment consultation with the tribes. EPA plans to roll back the protections to the equivalent of decades-old standards – or worse – based on incorrect science. Treaty Indian tribes in western Wash- ington believe a pollution-based economy is not sustainable and that no price can be placed on the value of human health or the resources that sustain us. Washington’s water quality standards were revised in 2016 – with EPA’s support – to include a more realistic fish consump- tion rate of 175 grams (about 6 ounces) per day. The cancer risk rate remained unchanged. The revised water quality standards were the result of years of extensive public processes at the state and federal levels, involving tribal governments as well as industry representatives, environmental groups and other stakeholders. There is no new science or law that jus- tifies EPA’s reconsideration or that would lead to a different result. If approved, the changes mean that every bite of seafood will contain higher levels of toxic chemicals and carcinogens. Salmon Recovery Treaty Indian tribes in western Wash- ington were greatly encouraged at the November 2019 Centennial Accord meeting when Gov. Jay Inslee committed to challenge the status quo and take steps needed for salmon recovery. Created in 1989 to mark the state’s 100th anniversary, the annual gathering brings together the tribes and state in a government-to-government forum to address issues of mutual interest such as health care, education and natural resources. The governor acknowledged the im- portance of healthy streamside areas as From the Chair NWIFC Chair Lorraine Loomis Chum spawn in Kennedy Creek in South Sound, where fisheries were canceled because of low returns. Photo: Debbie Preston

- 5. 52020 Annual Report critical to both our region’s salmon recov- ery efforts and our resiliency in the face of global climate change. He directed natural resources agencies to develop a proposal for a consistent approach to their manage- ment and protection based on clear and existing science. State of Washington data show that more than 1,700 miles of streams and rivers in western Washington do not meet state or federal water quality standards for water temperatures. Tribes have documented the decline of salmon habitat through the State of Our Watersheds report, which details hab- itat conditions and limiting factors for recovery throughout western Washington. We have developed solutions through gw ∂dz adad, our strategy for restoring salm- on habitat. More information about the State of Our Watersheds and gw ∂dz adad habitat strategy are available at: geo.nwifc.org/sow and nwtt.co/habitatstrategy. Salmon Coalition The Billy Frank Jr. Salmon Coalition of tribal, state and local policy leaders, sport and commercial fishermen, conservation groups and scientists was formed follow- ing the inaugural Billy Frank Jr. Pacific Salmon Summit in March 2018. At the second summit in November 2019, coalition members presented their priorities of restoring and protecting disappearing salmon habitat, enhancing hatchery production, and managing seal and sea lion populations. The coalition advocates for expanding salmon habitat by supporting protection of streamside habitat through uniform, science-based requirements across the region. The group also works to revise habitat standards in the state’s Growth Management Act and other land-use protection guidelines from one of No Net Loss to one of Net Gain. A statewide permit tracking system to create trans- parency, accountability and efficiency in tracking land-use decisions also is being considered. The Billy Frank Jr. Salmon Coalition supports increased state, federal and other funding to provide for increased salmon production and maintenance of state, federal, tribal and nonprofit hatchery facilities in the region. In particular, the coalition supports increased hatchery pro- duction, based on the latest science, in key watersheds to produce salmon for Indian and non-Indian fisheries and provide prey for southern resident orcas. Predation by pinnipeds such as har- bor seals and California sea lions on both adult and juvenile salmon is out of balance and slows salmon recovery significantly. It has been documented that seals and sea lions are eating more than six times the number of salmon harvested by fishermen. The coalition is developing recommen- dations to maintain stable seal and sea lion populations that won’t undermine salmon recovery efforts. As a first step, we are calling for an assessment of the status of pinniped populations in this region to determine optimal sustainable popula- tions. More information about the coalition is available at salmondefense.org/coalition. Culvert Case A 2018 U.S. Supreme Court decision requires the state of Washington to repair hundreds of fish-blocking culverts that vi- olate tribal treaty-reserved fishing rights. The Supreme Court affirmed that treaty rights require that fish be available for harvest and that the state can’t needlessly block streams and destroy salmon runs. In 2013, a lower federal court ordered the state Department of Transportation to reopen about 450 of its 800 most signifi- cant barrier culverts in western Washing- ton within 17 years. In early 2019, a two-year state budget was passed that would not adequately fund the culvert repairs ordered by the federal court. Fortunately, Gov. Inslee increased budget funding for these repairs by $175 million. Tribes remain concerned, however, about the long-term legislative direction for funding culvert replacement and the likelihood of the state meeting the court’s deadline. Our concerns are based on the state’s 2019-21 transportation budget that provided $8.5 million less than the pre- vious biennium and $175 million below the projected need of the Department of Transportation to maintain compliance with the court order. The state has continually delayed ag- gressively pursuing fish-passage barrier removal since the filing of the initial complaint in 2001. Every year the state Legislature delays funding for fish barrier removal causes a much larger financial problem for future budgets as costs rise and deadlines loom. Southern Resident Killer Whales As co-managers, tribes participated in a statewide Southern Resident Killer Whale Recovery Task Force in 2019 as the Salish Sea’s southern resident orcas declined to a low of 73. Treaty tribes have been call- ing for years for bold actions to recover chinook salmon, the orcas’ preferred prey, including increased hatchery production, habitat restoration and protection, and determining salmon predation impacts from seals and sea lions. In recommendations to Gov. Inslee, tribes said it is imperative that any ap- proaches to accelerating orca recovery be accomplished in a manner that respects tribal priorities and authorities as both a co-manager and more importantly, as sov- ereign nations with reserved treaty rights and resources. Conclusion Despite the challenges we face, the trea- ty tribes in western Washington remain committed to recovering salmon and their habitat, and restoring a balanced regional ecosystem. But that commitment comes with a caution. As our late leader Billy Frank Jr. said: “As the salmon disappear, so do our tribal cultures and treaty rights. We are at a crossroads and we are running out of time.” Squaxin Island Tribe Chair Arnold Cooper signs a commitment to action at the second Billy Frank Jr. Pacific Salmon Summit in November 2019. Photo: Debbie Preston

- 6. 6 Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission Harvest Management: Salmon Treaty Indian tribes and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife co-manage salmon fisheries in Puget Sound, the Strait of Juan de Fuca and nearshore coastal waters. • For decades, state and tribal salmon co-managers have reduced harvest in response to declining salmon runs. Tribes have cut harvest by 80 to 90 percent since 1985. • Under U.S. v. Washington (the Boldt decision), harvest occurs only after sufficient fish are available to sustain the resource. • The tribes monitor their harvest using the Treaty Indian Catch Monitoring Program to provide accurate, same-day catch sta- tistics for treaty Indian fisheries. The program enables close monitoring of tribal harvest levels and allows for in-season adjustments. • Tribal and state managers work cooperatively through the Pacific Fishery Management Council and the North of Falcon process to develop fishing seasons. The co-managers also cooperate with Canadian and Alaskan fisheries managers through the U.S./Can- ada Pacific Salmon Treaty. After a 25-year absence, tribal and nontribal fishermen can again harvest chinook in McAllister Creek, thanks to the Nisqually Tribe. The headwaters of McAllister Creek were known historically to the tribe as Medicine Springs. The area was trans- ferred back to the tribe in 2016 from the city of Olympia after decades of work by tribal and city staff. The mouth of the creek is the site where the Treaty of Medicine Creek was signed in 1854. Today it’s part of the Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually Wildlife Refuge. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) closed its hatchery in McAllister Creek in the mid-1990s, ending fishing opportunity there. Each year since 2016, Nisqually has transported up to 1 million chinook smolts to the springs from its Clear Creek Hatchery. They are held in a pond in Medicine Springs for several weeks before being released. These hatchery fish already are provid- ing a much-needed tribal fishing oppor- tunity in the Nisqually watershed, where Nisqually River fisheries often are closed to allow weak salmon runs to recover. “There are 2-, 3- and 4-year old chinook returning to McAllister Creek this year,” said Bill St. Jean, enhancement program manager for the tribe. “Access is a little tough for sport fishermen, but the guys getting under the bridge there are success- ful pretty quickly.” Other fishermen are taking small boats out to the mouth of the creek, catching bright, shiny chinook up to 25 pounds. The tribe is involved in a number of efforts to restore and protect habitat in the ocean, Puget Sound and the river delta to improve the health and long-term returns of these salmon. Partners include Nisqually River Council, Nisqually Land Trust, the cities of Tacoma, Centralia and Eatonville, the Salmon Recovery Funding Board, WDFW, South Puget Sound Salm- on Enhancement Group and others. The tribe operates two hatchery facili- ties in the Nisqually River in addition to the Medicine Springs site. The hatchery programs use the latest science and are a critical part of the recovery efforts for the Puget Sound Fall Chinook Evolutionary Significant Unit. Salmon are culturally and economically important to tribal members who fought for the treaty-reserved right to fish during the Fish Wars, which led to the 1974 Boldt decision that affirmed those rights, and was later upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court. Chinook run returns to creek where treaty was signed Nisqually tribal fishermen Joseph Squally (right) and his grandfather Albert “Chief” Squally work to repair a net on McAllister Creek during the chinook fishery. Photo: Debbie Preston

- 7. 72020 Annual Report Harvest Management: Shellfish Treaty tribes harvest native littleneck, manila, razor and geo- duck clams, Pacific oysters, Dungeness crab, shrimp and other shellfish throughout the coast and Puget Sound. • Tribal shellfish programs manage harvests with other tribes and the state through resource-sharing agreements. The tribes are exploring ways to improve management of other species, including sea cucumbers, Olympia oysters and sea urchins. • Tribal shellfish enhancement results in bigger and more consistent harvests that benefit both tribal and nontribal diggers. • Shellfish harvested in ceremonial and subsistence fisheries are a necessary part of tribal culture and traditional diet. • Shellfish harvested in commercial fisheries are sold to li- censed buyers. For the protection of public health, shellfish are harvested and processed according to strict state and national standards. • Tribes continue to work with property owners to manage harvest on nontribal tidelands. • In 2018 (the most recent year for which data is available), treaty tribes in western Washington commercially harvest- ed more than 1.4 million pounds of manila and littleneck clams, more than 2.7 million pounds of geoduck clams, more than 3 million oysters, 6.4 million pounds of crab, 234,000 pounds of sea cucumbers, 480,000 pounds of green and red sea urchins, and 330,000 pounds of shrimp. Tribes throughout the Salish Sea and Washington coast are supporting stud- ies to better understand Dungeness crab populations. Crab always have been a part of tribal members’ diet and culture and are an important part of tribal economies in western Washington, since salmon fishing is limited by habitat destruction and his- torical overharvest. The Dungeness crab fishery is important to tribal and nontrib- al commercial fishermen, contributing the largest value of catch in the state, estimat- ed at $12.5 million in 2017-2018. In recognition of the need to improve Dungeness crab science and management, the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community and Lummi Nation launched a cooper- ative research effort among tribal, state, federal and academic researchers. The Pacific Northwest Crab Research Group aims to promote sustainable Dungeness crab populations. Since the group’s incep- tion in December 2018, it has grown to in- clude more than 60 individuals, primarily representing tribal governments. The research group partnered with Washington Sea Grant (WSG) to support a fellow to serve as a program coordina- tor, developing a work plan for the group, ensuring standardization of methods, creating data-sharing protocols and man- aging data. The research group’s first initiative is a statewide long-term monitoring effort examining regional variation in larval Dungeness crab abundance. Biologists are using light traps to count tiny Dungeness crab larvae, called megalopae. The traps are made from water jugs with an internal light on a timer. When the light turns on at night, it attracts crab larvae and other small marine life. Samplers are following a model devel- oped by Alan Shanks at the University of Oregon that found a link between the number of crab larvae collected in light traps and commercial crab catch on the Oregon coast. “While it will take at least 10 years of data collection before we will know if Dr. Shanks’ model works in Washington for predicting coastal or inland commercial crab catch, the larval data we collect now will answer important questions about larval crab populations and the timing of larval pulses throughout Washington wa- ters,” said Julie Barber, Swinomish senior shellfish biologist. Tribes organize regionwide Dungeness crab research Nisqually shellfish biologist Margaret Homerding and natural resources technician Eddie Villegas record the size, sex and condition of a crab during a survey. Photo: Debbie Preston

- 8. 8 Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission Harvest Management: Marine Fish Treaty tribes are co-managers of the marine fish resource, working closely with state and federal agencies, and in interna- tional forums to develop and implement species conservation plans for all marine fish stocks in Puget Sound and along the Pacific coast. • Many areas of Puget Sound have experienced a stark drop in marine fish populations. Herring and smelt, historically the most plentiful forage fish, have sharply declined over the past two decades. Several species of rockfish are list- ed as threatened or endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act. Human activity, such as pollution and develop- ment, is believed to be a leading cause of the overall decline. • The Pacific Fishery Management Council, which includes the tribal and state co-man- agers, regulates the catch of black cod, rockfish and other marine fish. Halibut are managed through the International Pacific Halibut Commission, established by the U.S. and Canadian governments. Tribes are active participants in season-setting pro- cesses and the technical groups that serve those bodies. • Treaty tribes manage marine fisheries that include purse-seining for sardines and an- chovy, midwater fisheries for rockfish and Pacific whiting, and groundfish fisheries that include sablefish, sole, Pacific cod and rockfish. • The coastal tribes and state support ocean monitoring and research leading to an ecosystem-based management of fishery resources. This includes integrating all coastal ocean research into a common database called the Habitat Framework Initiative. The initiative puts available habitat data into a common catalog for state, federal and tribal managers who often share jurisdictions and manage resources jointly. The Quinault Indian Nation is looking into the effects climate change will have on the ocean, and what will be available for the fishermen who have plied the sea forever. “There are a lot of climate adaptation plans for the land and even nearshore, but little for complex ocean fisheries,” said Joe Schumacker, Quinault marine resources scientist. The tribe plans to contract with spe- cialists to help predict changes to ocean populations and fisheries. “By taking into account climatology, oceanography, biological changes and other data, we can look at species of interest and forecast their vulnerability,” Schumacker said. The architecture of ocean life is chang- ing as climate change threatens certain parts of the food web more than others. This includes foundational life such as copepods and krill, small marine animals consumed by forage fish, salmon and even baleen whales. “What will Quinault and other tribes be managing in the future?” Schumacker said. “The treaty right doesn’t move – will it remain productive with the current species, or will it be different?” Quinault participates in a variety of ocean fisheries including salmon, halibut, black cod and crab. As the waters have warmed, tuna fisheries have become more reliable and often closer to shore. Increas- ingly, large “blobs” of warm, low-oxygen water also have parked offshore near Quinault territory in recent years, nega- tively affecting those important food webs and, in worst cases, causing large die-offs of fish. By gathering and synthesizing data about changing conditions, Quinault can manage fisheries proactively. New species may be available while others may dwindle or move because of changing conditions. “We have some data that feeds into monitoring and forecasting tools for large-scale areas like the entire West Coast but we need downscaled data for our Quinault traditional fishing area,” Schumacker said. “Right now, satellites provide an ex- pensive and sometimes unreliable data connection, but in the next 10 years, we’ll have greater access to fiber-optic cables in the ocean and, potentially, low orbit wifi satellites or balloons.” The Bureau of Indian Affairs has ap- proved the tribe’s proposal for the project and is seeking bids. Planning for marine effects of climate change The ocean habitat in the Quinault Indian Nation’s traditional area will be the subject of a localized model to see how climate change will affect ocean species of interest. Photo: Debbie Preston

- 9. 92020 Annual Report Hatchery Management Hatcheries must remain a central part of salmon manage- ment in western Washington as long as lost and degraded habitat prevent watersheds from naturally producing abun- dant, self-sustaining salmon runs of sufficient size to meet tribal treaty fishing rights. • Treaty Indian tribes released more than 43 million salmon and steelhead in 2018 (the most recent year for which data is available), including 14.8 million chinook, 19.3 million chum and 8 million coho, as well as more than 800,000 sockeye and more than 600,000 steel- head. • Most tribal hatcheries produce salmon for harvest by both Indian and non-Indian fishermen. Some serve as wild salmon nurseries that improve the survival of juvenile fish and increase returns of salmon that spawn naturally in our watersheds. • Tribes conduct an extensive mass marking and coded- wire tag program. Young fish are marked by having their adipose fin clipped before release. Tiny coded-wire tags are inserted into the noses of juvenile salmon. The tags from marked fish are recovered in fisheries, providing important information about marine survival, migration and hatchery effectiveness. The Skokomish Tribe and Tacoma Power are bringing sockeye salmon back to the North Fork Skokomish River and Hood Canal. “Our goal is to restore a sustainable run that we haven’t seen since the river’s dams were built,” said Dave Herrera, the tribe’s fisheries policy representative. The Lake Cushman and Lake Kokanee dams were built in the 1920s to provide hydroelectric power for the city of Tacoma, but lacked fish passage facilities and dewatered the North Fork. A 2009 hydroelectric dam relicensing agreement between the tribe and utility led to river restoration, increased water flow, fish passage improvements, fish and wildlife habitat restoration, and salmon hatchery programs on the North Fork. “The long-term goal is to pass fish around the dams between the upper and lower watersheds of the North Fork, but the population numbers need to increase first, so we’ve implemented recovery programs for chinook, coho, sockeye and steelhead,” said Andrew Ollenburg, Taco- ma’s Cushman Fish Facilities manager. Every fall since 2016, the sockeye hatchery on Hood Canal has incubated eggs from Puget Sound Energy’s Baker River stock. The following spring, sockeye fry are placed in rearing tanks until the summer when they are transferred to Lake Cushman to acclimatize. The fish are released into the river to out-migrate to the canal and ocean for three to four years before they come back to the river as adults. The hatchery also makes a thermal mark on the fish ear bone, or otolith, by dropping the water temperature for varying lengths of time, so staff can later determine the age of returning fish. The fish are not clipped so they will not be harvested, allowing more sockeye to return to the river. Any sockeye that show up at the hatchery will be brought into the spawning program. Sockeye that returned in 2019 from the 2016 release are considered 3-year-olds, Ollenburg said, with more expected next year as 4-year-olds. “After nearly 100 years of conflict over the Cushman dams, the settlement agree- ment has led to a real partnership between the utility and the tribe,” Herrera said. “The tribe took the lead in securing the broodstock for the hatcheries, supported the securing of federal energy funds to help pay for the construction of the fish passage facilities, and the tribe’s fisheries staff now do monitoring work for Taco- ma in the North Fork and estuary of the Skokomish River,” he said. Partnership with city helps recover sockeye salmon Juvenile sockeye salmon at Tacoma’s Saltwater Park Sockeye Hatch- ery are part of the city and the Skokomish Tribe’s program to restore a sustainable run in the Skokomish River. Photo: Tiffany Royal

- 10. 10 Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission Habitat Management Habitat protection and restoration are es- sential for recovering wild salmon in western Washington. Tribes are taking action to recover salmon in each watershed, and have restored thousands of miles of habitat. • Tribes are collaborating with the state of Washington to fix the fish-blocking cul- verts that were the subject of a 2018 U.S. Supreme Court case. The Supreme Court affirmed a ruling that state blockages of salmon habitat violate tribal treaty rights. The state was ordered to remove barriers to fish passage. • The NWIFC Salmon and Steelhead Hab- itat Inventory and Assessment Program (SSHIAP) provides a database of local and regional habitat conditions. SSHIAP has launched an interactive map to track repairs to state-owned culverts, a tool to map potential steelhead habitat, a data exchange for research about the nearshore environment, and also publishes the State of Our Water- sheds report at geo.nwifc.org/sow. • Tribes conduct extensive water quality monitoring for pollution and to ensure factors such as dissolved oxygen and temperature levels are adequate for salmon and other fish. To make limited federal funding work to its fullest, tribes partner with state agencies, industries and property owners through collaborative habitat protection, resto- ration and enhancement efforts. • In western Washington, the National Oceanic and Atmo- spheric Administration’s Pacific Coastal Salmon Recovery Fund has supported projects that have restored and protected fish access to more than 1 million acres of spawning and rearing habitat, and removed hundreds of fish-passage barriers. Juvenile salmon are using the new habi- tat at zis a ba in the Stillaguamish estuary, where the Stillaguamish Tribe restored tidal flow in October 2017. Formerly part of the tidal marshes connected to Port Susan and south Skagit Bay, zis a ba had been isolated from the river and tides by a dike built more than 100 years ago to protect a homestead from flooding. The tribe purchased the property in 2012 with the intention of setting back the dikes to create more rearing habitat for juvenile salmon, especially chinook. It was named zis a ba for a former tribal chief. “When the fish come out from their spawning areas in the North and South Fork Stillaguamish in the spring, they need places to grow larger before they head offshore, and these tidal wetlands are an important stop on that journey to the ocean,” said Jason Griffith, Stillaguamish fisheries biologist. “This is an area that fish historically used to use, but they have been cut off from it for a very long time.” Tribal natural resources staff along with staff from the Skagit River System Coop- erative (SRSC) are monitoring the area to see if the restoration project is working as designed. This work includes collecting genetic information from juvenile salmon to measure the benefit of the project be- yond the Stillaguamish River. Biologists use seines to collect fish in several sites on a biweekly basis. When they find juvenile chinook, they take a small fin clip for DNA testing before returning them to the estuary. “The DNA will tell us what river system they came from,” Griffith said. “This area is kind of a mixing ground for the Whid- bey basin.” “Even though the project is intended to improve Stillaguamish River stocks, Skagit River chinook have access and use this estuary as well,” said Mike LeMoine, a biologist with SRSC, which is the natural resources extension of the Swinomish and Sauk-Suiattle tribes. Research in other river systems, includ- ing the Skagit and Snohomish, has shown that increasing tidal wetlands leads to fewer fish dying before they reach adult- hood, and therefore larger numbers of chinook returning to spawn, Griffith said. “These projects are pretty important for chinook recovery, for orca recovery, and for ensuring that the tribes and nontreaty fishers have lots of opportunities,” he said. Estuary restoration gives juvenile salmon place to rear Biologists from the Stillaguamish, Swinomish and Sauk-Suiattle tribes collect fish in a beach seine, looking for juvenile salmon using the estuary. Photo: Kari Neumeyer

- 11. 112020 Annual Report Wildlife Management The treaty Indian tribes are co-managers of wildlife resources in west- ern Washington, including deer, elk, bear and mountain goats. • Tribal wildlife departments work with state agencies and citizen groups on wildlife forage and habitat enhancement projects, reg- ularly conducting wildlife population studies using GPS collars to track migration patterns. • Tribes implement occasional hunting moratoriums in response to declining populations because of degraded and disconnected habitat, invasive species and disease. • Western Washington treaty tribal hunters account for a small portion of the total combined deer and elk harvest in the state. In the 2018 season, treaty tribal hunters harvested a reported 375 elk and 548 deer, while non-Indian hunters harvested a reported 5,559 elk and 27,846 deer. • Tribal hunters hunt for sustenance and most do not hunt only for themselves. Tribal culture in western Washington is based on extended family relationships, with hunters sharing game with several families. Some tribes have designated hunters who harvest wildlife for tribal elders and others unable to hunt for themselves, as well as for ceremonial purposes. • As a sovereign government, each treaty tribe develops its own hunting regulations and ordinances for tribal members. Tribal hunt- ers are licensed by their tribes and must obtain tags for animals they wish to hunt. • Many tribes conduct hunter education programs aimed at teaching tribal youth safe hunting practices. Wildlife managers are sampling elk to learn more about the hoof disease prolif- erating across the region. Often referred to as “hoof rot,” cases of treponeme-associated hoof disease (TAHD) have increased among elk in Southwest Washington since 2008. The disease has been seen in the Olympic Peninsula and North Cascades herds over the past three years. The Swinomish Tribe is watching out for potentially diseased animals in the North Cascades herd by examining all an- imals harvested by community members for early signs of hoof disease. Suspicious hooves are sent to the Washington State University’s Animal Disease Diagnostic Lab. “Swinomish is working closely with co-managers to better understand the prevalence and distribution of hoof dis- ease in the North Cascades, and detecting animals in the early stages of the disease is critical to that process,” said Leslie Parks, a Swinomish biologist. “We hope to use this information to develop strategies to minimize the impact of hoof disease on the herd. “ Samples also have been collected by other tribes including the Upper Skagit Tribe in the North Cascades, the Muck- leshoot Tribe in South Sound and the Skokomish Tribe in Hood Canal. The disease likely is transmitted via the soil from bacteria that sheds from the hooves of infected elk and is transmitted to other animals in the herd. “Euthanizing elk with hoof disease may help stop the spread of the disease,” said NWIFC veterinarian Dr. Nora Hickey. “This strategy has been tried with wildlife diseases in other regions, such as chronic wasting disease in deer in the Midwest, with fairly good success.” There is no vaccine against hoof dis- ease and there is no proven way to treat free-ranging animals. Dr. Margaret Wild of WSU’s Depart- ment of Veterinary Microbiology and Pathology at the College of Veterinary Medicine in Pullman is researching hoof disease. She is trying to determine wheth- er one strain of hoof disease has spread across the region, or whether these are independent outbreaks. The disease causes sores and lesions leading to significant pain and suffering. Afflicted elk can lose the hard capsule covering their hooves and have difficulty walking, which makes them unable to find food and escape predators. Washington state recently passed a law aimed at limiting the spread of hoof dis- ease by requiring hunters in areas where it is present to remove hooves and leave them where the elk was killed. The public can help by reporting limping elk or hoof deformities to the state at nwtt.co/elkhoof. Leslie Parks, Swinomish wildlife biologist, samples an elk to test for hoof disease. Photo: Chris Madsen Tribes track elk hoof disease across the region

- 12. 12 Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission Regional Collaboration Puget Sound is the second largest estuary in the United States and its health has been declining for decades. Recognizing this, Congress designated Puget Sound as an Estuary of National Significance, further acknowledging the critical contributions that Puget Sound provides to the environmental and economic well-being of the nation. Through the National Estuary Program, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) works with tribal, state and local partners to help restore and protect this iconic and ecologically important place. • In 2007, the state of Washington created the Puget Sound Partnership dedicated to working with tribal, state, federal and local governments and stakeholders to clean up and restore the environmental health of Puget Sound by the year 2020. This diverse group continues to work toward a coordinated and cooperative recovery effort through the Partnership’s Action Agenda, which is focused on decreasing polluted storm- water runoff, and protecting and restoring fish and shellfish habitat. • The Tribal Management Conference was created in 2016 through EPA’s model for the National Estuary Program for Puget Sound. It increases the ability of tribes to provide direct input into the program’s decisional framework. The Tribal Management Conference is working with the Puget Sound Partnership to implement a list of “bold actions” that can turn around salmon recovery in Puget Sound. The bold actions fall under several broad categories: Protect remaining salmon habitat, create a transparent and open accountability system on habitat, stop all water uses that limit salmon recovery, reduce salmon predation, improve monitoring and increase funding for habitat restoration. • Western Washington treaty tribes participate in Puget Sound Day on the Hill, a two-day advocacy effort each spring in Washington, D.C. The tribes also participated in the first-ever Puget Sound Day on the Sound in Puyallup, where partners discussed regional issues with federal, state and local leaders. Puget Sound Recovery Data from the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe’s 2014 intensive salmon habitat study helped get a $15 million Puget Sound nearshore restoration project off the ground in 2019. Since 1940, a causeway and two under- sized culverts in the salt marsh between Kilisut and Oak harbors, near Marrow- stone and Indian islands, hindered salm- on migration and restricted tidal flow. From 2011-2014, the tribe surveyed ju- venile salmon in nearshore environments in Hood Canal and Admiralty Inlet. Unexpectedly, juvenile salmon were found migrating away from large estuaries, like the Duckabush and Dosewallips, and into embayments such as Kilisut Harbor to hide, rest and feed, said Hans Dauben- berger, the tribe’s senior research scientist. “Restoring the connection between Kilisut Harbor and Oak Bay will allow out-migrating salmonids access to high quality coastal waters and nearshore habitat with abundant, energy-rich prey,” he said. A 450-foot-long bridge will replace the causeway and undersized culverts, open- ing up 2,300 acres of habitat, improving fish passage, water quality and tidal flow. This benefits Puget Sound and Strait of Georgia salmon, Puget Sound chinook and steelhead, Hood Canal summer chum, forage fish and shellfish. Work began in summer 2019, with bridge work continuing through the winter. The culverts are expected to be removed in summer 2020. “The data provided by the tribe from that study is responsible for helping make this project happen,” said Rebecca Benjamin, executive director of the North Olympic Salmon Coalition (NOSC), which is spearheading the project. NOSC was able to secure $15 million in funding from more than 20 sources and partners. The Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe supplied $2 million, of which $1 million was from U.S. Navy mitigation funds from the Port Gamble S’Klallam, Jamestown S’Klallam and the Lower Elwha Klallam tribes, and $1 million from the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe through a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration grant. Support also was provided by local landowners, the U.S. Navy and Marrowstone Island residents. Tribe’s survey leads to Puget Sound nearshore project Partners supporting the Kilisut Harbor restoration project, including Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe chairman Jeromy Sullivan, center, hold a groundbreaking ceremony in summer 2019. Photo: Tiffany Royal

- 13. 132020 Annual Report The Coordinated Tribal Water Quality Program was created by the Pacific Northwest tribes and the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to address water quality issues under the Clean Water Act. • EPA’s General Assistance Program (GAP) was established in 1992 to improve capacity for environmental protection programs for all tribes in the country. Many tribes are now participating in the “Beyond GAP” project to build on these investments by creating environmental implementation programs locally while supporting national environmental protection objectives. • These programs are essential to combat threats to tribal treaty resources such as declining water quality and quan- tity. In western Washington, climate change and urban development negatively affect water resources and aquat- ic ecosystems and will get worse with a state population expected to rise by nearly 1 million in the next 10 years. • Tribal water resources program goals include establishing instream flows to sustain harvestable populations of salm- on, identifying limiting factors for salmon recovery, protect- ing existing groundwater and surface water supplies, and participating in multi-agency planning processes for water quantity and quality management. Water Resources Forest Management Two processes – the Timber/Fish/Wildlife (TFW) Agreement and the Forests and Fish Report (FFR) – provide the frame- work for adaptive management by bringing together tribes, state and federal agencies, environmental groups and private forestland owners to protect salmon, wildlife and other species while providing for the economic health of the timber industry. • Treaty tribes in western Washington manage their forest- lands to benefit people, fish, wildlife and water. • Reforestation for future needs is part of maintaining healthy forests, which are key to maintaining vibrant streams for salmon and enabling wildlife to thrive. • Forestlands are a source of treaty-protected foods, medi- cine and cultural items. • A tribal representative serves on the state’s Forest Prac- tices Board, which sets standards for activities such as timber harvest, road construction and forest chemical applications. Tribes also are active participants in the FFR Cooperative Monitoring, Evaluation and Research Commit- tee. Mount Rainier overlooks Budd Inlet at sunset. Puget Sound recovery faces the same challenges as ever, but these are amplified by explosive growth and climate change. Photo: Debbie Preston

- 14. 14 Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission The state of Washington, the Hoh, Makah and Quileute tribes, and the Quinault Indian Nation work with the National Oceanic and Atmo- spheric Administration to integrate common research goals to understand changing ocean conditions and create the building blocks for managing these resources. • In recognition of the challenges facing the Olympic coast ecosystem, the tribes and state of Washington established the Inter- governmental Policy Council (IPC) to guide management of Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary (OCNMS). Many of the research and planning goals established by tribes and the state support U.S. Ocean Policy. In 2019, the tribes worked with their partners to reauthorize the IPC through 2022. The tribes also are active members of the OCNMS Advisory Council, regional Marine Resource Committees, the Washington Coastal Marine Advisory Council and the West Coast Ocean Alliance. • Climate change, ocean warming, ocean acidification, hypoxia and harmful algal blooms have been top priorities the past several years. Because of their unique vulnera- bility, coastal indigenous cultures are leaders in societal adaptation and mitigation in response to events driven by climate change. As ocean conditions change due to cli- mate change and disruptions such as the Pacific decadal oscillation, El Niño, the “Blob” and seasonal upwelling, it will be important to understand the changes that are occurring and how they affect the ecosystem. Tribes are working with the Northwest Association of Networked Ocean Observing Systems and other state and federal partners to improve monitoring of marine conditions and access to data products necessary for effective deci- sion-making. • The tribes continue to work with the state of Washington and federal partners to respond to the findings of the state’s Blue Ribbon Panel on Ocean Acidification. Several tribes are members of the International Alliance to Com- bat Ocean Acidification, including serving on its Governing Council. Tribes also are working with the state Depart- ment of Natural Resources to monitor ocean acidification conditions in nearshore waters as part of the Acidification Nearshore Monitoring Network (ANeMoNe) program. • The tribes and the federal government are using a new marine habitat analytical tool called the “Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard” to improve management of treaty-protected natural resources. This new standard defines habitat by translating data sets into four components – water column, geoform, substrate and biotic attributes – that provide a more comprehensive understanding of habitats and their ecosystem function. Learn more at nwtt.co/oceanmaps. Ocean Resources The Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe wants to know how ocean acidification might be affecting shellfish in Sequim Bay. Ocean acidification, the decrease of the ocean’s pH level caused by the absorption of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, can change marine water chemistry, affecting shellfish survival and growth at the microscopic larvae stage. Longer term effects of ocean acidifica- tion can reduce shell and body growth, and impact the resource as a whole, im- peding the tribe’s ability to harvest. On the Sequim Bay tidelands, the tribe manages more than 60 acres of shellfish cultivation for commercial, subsistence and restoration purposes, including geoduck, littleneck and manila clams, and Pacific and Olympia oysters. “The tribe depends on natural and farmed shellfish to provide economic opportunities and maintain cultural har- vest practices,” said Liz Tobin, the tribe’s shellfish biologist. “The threat of ocean acidification in Puget Sound has the po- tential to greatly affect the availability and sustainability of tribal shellfish resources.” The tribe is participating in the Wash- ington Department of Natural Resources’ Acidification Nearshore Monitoring Net- work (ANeMoNe) – a network of sensors installed in several nearshore environ- ments in Puget Sound and on the coast. The sensors measure changes in marine chemistry at different locations and can be used to evaluate potential impacts on marine organisms. “Taking part in the ANeMoNe network allows us to gather important baseline data on Sequim Bay seawater chemistry, such as time series data that would allow us to detect trends or events in declining pH,” Tobin said. “There is evidence of increased season- al declines in seawater pH on the outer coast,” she said. “Such corrosive waters have been detected on the coast but we don’t have a strong handle if similar events are occurring in nearshore envi- ronments of Puget Sound.” Tracking long-term effects of ocean acidification Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe shellfish staff count eelgrass plants as part of the ANeMoNe study. Photo: Tiffany Royal

- 15. 152020 Annual Report The Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission (NWIFC) was created in 1974 by the 20 treaty Indian tribes in western Washington that were parties to U.S. v. Washington. The litigation affirmed their treaty-reserved salmon harvest rights and established the tribes as natural resources co-managers with the state. The NWIFC is an intertribal organiza tion that assists member tribes with their natural resources co-management respon sibilities. Member tribes select commis sioners who develop policy and provide direction for the organization. The commission employs about 75 full-time employees and is headquartered in Olympia, Wash., with satellite offices in Forks, Poulsbo and Burlington. It provides broad policy coordination as well as high-quality technical and support services for member tribes in their efforts to co-manage the natural resources in western Washington. The commission also acts as a forum for tribes to address issues of shared concern, and enables the tribes to speak with a unified voice. Fisheries Management • Long-range planning, salmon recovery efforts and federal Endangered Species Act implementation. • Develop pre-season agreements, pre season and in-season run size forecast monitoring, and post-season fishery analysis and reporting. • Participate in regionwide fisheries management processes with entities such as the International Pacific Halibut Commission and Pacific Fishery Management Council. • Marine fish and shellfish management planning. • Facilitate tribal participation in the U.S./Canada Pacific Salmon Treaty including organizing intertribal and interagency meetings, developing issue papers and negotiation options for tribes, serving on technical committees and coordinating tribal research associated with implementing the treaty. Quantitative Services • Administer and coordinate the Treaty Indian Catch Monitoring Program. • Provide statistical consulting services. • Conduct data analysis of fisheries studies and develop study designs. • Update and evaluate fishery management statistical models and databases. Habitat Services • Coordinate policy and technical discussion between tribes and federal, state and local governments, and other interested parties. • Coordinate and monitor tribal interests in the Timber/Fish/Wildlife and Forests and Fish Report processes, Coordinated Tribal Water Resources, and Cooperative Monitoring, Evaluation and Research Committee ambient monitoring programs. • Analyze and distribute technical information on habitat-related forums, programs and processes. • Implement the Salmon and Steelhead Habitat Inventory and Assessment Project. Enhancement Services • Assist tribes with production and release of an average of 40 million salmon and steelhead each year. • Coordinate coded-wire tagging of more than 4 million fish at tribal hatcheries to provide information critical to fisheries management. • Analyze coded-wire tag data. • Provide genetic, ecological and statistical consulting for tribal hatchery programs. • Provide fish health services to tribal hatcheries for juvenile fish health monitoring, disease diagnosis, adult health inspection and vaccine production. Information and Education Services • Provide internal and external communication services to member tribes and NWIFC. • Develop and distribute communication products such as news releases, newsletters, videos, photos, social media and web-based content. • Respond to public requests for information about the tribes, their treaty rights, natural resources management activities and environmental issues. • Work with federal and state agencies, environmental organizations and others in cooperative communication efforts. • Respond to state and federal legislation. Wildlife Management • Manage and maintain the intertribal wildlife harvest database and the collection of tribal hunting regulations. • Provide assistance to tribes on wildlife issues. • Respond to and facilitate tribal discussions on key management, litigation and legislation issues. • Provide technical assistance, including statistical review and data analysis, and/or direct involvement in wildlife and habitat management projects. Hatchery Reform Endangered Species Act Pacific Salmon Treaty Fish, Shellfish and Wildlife Harvest Management Harvest Monitoring/Data Collection Population Monitoring and Research Policy Development and Intergovernmental Relations Fisherman and Vessel Identification Natural Resources Enforcement Coordination Water Resources Protection and Assessment Forestland Management Administrative Support Puget Sound Recovery Watershed Recovery Planning Other State and Local Collaborative Programs Coordinated Tribal Water Resources Salmon Mass Marking Ocean Ecosystem Initiative Marine Mammal Protection Act Stevens Treaties NWIFC Activities

- 16. Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission Clouds hover over the Washington coast, where treaty tribes are concerned about sea level rise, warming water temperatures and ocean acidification as a result of climate change. Photo: Debbie Preston