Prescrition co-owners- pdf

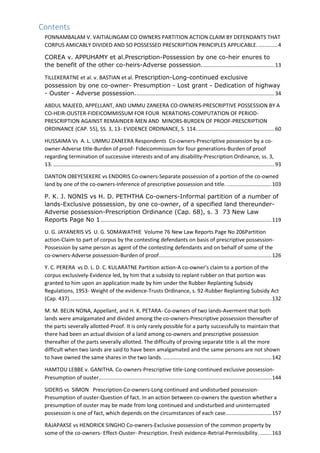

- 1. Contents PONNAMBALAM V. VAITIALINGAM CO OWNERS PARTITION ACTION CLAIM BY DEFENDANTS THAT CORPUS AMICABLY DIVIDED AND SO POSSESSED PRESCRIPTION PRINCIPLES APPLICABLE..............4 COREA v. APPUHAMY et al.Prescription-Possession by one co-heir enures to the benefit of the other co-heirs-Adverse possession.................................................13 TILLEKERATNE et al. v. BASTIAN et al. Prescription-Long-continued exclusive possession by one co-owner- Presumption - Lost grant - Dedication of highway - Ouster - Adverse possession..............................................................................................34 ABDUL MAJEED, APPELLANT, AND UMMU ZANEERA CO-OWNERS-PRESCRIPTIVE POSSESSION BY A CO-HEIR-OUSTER-FIDEICOMMISSUM FOR FOUR NERATIONS-COMPUTATION OF PERIOD- PRESCRIPTION AGAINST REMAINDER-MEN AND MINORS-BURDEN OF PROOF-PRESCRIPTION ORDINANCE (CAP. 55), SS. 3, 13- EVIDENCE ORDINANCE, S. 114.....................................................60 HUSSAIMA Vs A. L. UMMU ZANEERA Respondents Co-owners-Prescriptive possession by a co- owner-Adverse title-Burden of proof- Fideicommissum for four generations-Burden of proof regarding termination of successive interests and of any disability-Prescription Ordinance, ss. 3, 13. .....................................................................................................................................................93 DANTON OBEYESEKERE vs ENDORIS Co-owners-Separate possession of a portion of the co-owned land by one of the co-owners-Inference of prescriptive possession and title. ..............................103 P. K. J. NONIS vs H. D. PETHTHA Co-owners-Informal partition of a number of lands-Exclusive possession, by one co-owner, of a specified land thereunder- Adverse possession-Prescription Ordinance (Cap. 68), s. 3 73 New Law Reports Page No 1 ...................................................................................................................119 U. G. JAYANERIS VS U. G. SOMAWATHIE Volume 76 New Law Reports Page No 206Partition action-Claim to part of corpus by the contesting defendants on basis of prescriptive possession- Possession by same person as agent of the contesting defendants and on behalf of some of the co-owners-Adverse possession-Burden of proof............................................................................126 Y. C. PERERA vs D. L. D. C. KULARATNE Partition action-A co-owner's claim to a portion of the corpus exclusively-Evidence led, by him that a subsidy to replant rubber on that portion was granted to him upon an application made by him under the Rubber Replanting Subsidy Regulations, 1953- Weight of the evidence-Trusts Ordinance, s. 92-Rubber Replanting Subsidy Act (Cap. 437)........................................................................................................................................132 M. M. BELIN NONA, Appellant, and H. K. PETARA- Co-owners of two lands-Averment that both lands were amalgamated and divided among the co-owners-Prescriptive possession thereafter of the parts severally allotted-Proof. It is only rarely possible for a party successfully to maintain that there had been an actual division of a land among co-owners and prescriptive possession thereafter of the parts severally allotted. The difficulty of proving separate title is all the more difficult when two lands are said to have been amalgamated and the same persons are not shown to have owned the same shares in the two lands..........................................................................142 HAMTOU LEBBE v. GANITHA. Co-owners-Prescriptive title-Long-continued exclusive possession- Presumption of ouster....................................................................................................................144 SIDERIS vs SIMON Prescription-Co-owners-Long continued and undisturbed possession- Presumption of ouster-Question of fact. In an action between co-owners the question whether a presumption of ouster may be made from long continued and undisturbed and uninterrupted possession is one of fact, which depends on the circumstances of each case...............................157 RAJAPAKSE vs HENDRICK SINGHO Co-owners-Exclusive possession of the common property by some of the co-owners- Effect-Ouster- Prescription. Fresh evidence-Retrial-Permissibility.........163

- 2. JAMIS PERERA AND ANOTHER v. CHARLES DIAS AND OTHERS Prescription - Prescription among co- owners - Division and adverse possession of co-owned property. ................................................171 LEISA AND ANOTHER v. SIMON AND ANOTHER Rei Vindicatio - Prescriptive rights - Presumption of right to possess - Difference between possession, occupation and dominium - Prescription Ordinance, section 3 - Plaintiff claims paper title as well as by prescription - Should the plaintiff prove prescription...........................................................................................................................175 FERNANDO v. FERNANDO New Law Reports Volume 44, Page No 65 Co-owners-Purchaser of entire property from a Co-owner-Prescription- Ouster. ................................................................187 MARIA PERERA v. ALBERT PERERA Partition Amicable partition Ouster Prescription Sri Lanka Law Reports 1983 - Volume 2 , Page No - 399 ..........................................................................................194 BANDARA, Vs SINNAPPU 47 NLR 249 Where a Iand Panguwa consisted of gardens, deniyas and chenas and it was established that these deniyas were assweddumized by the various co-owners and possessed separately by them without interference by the other co-owners for a period of over twenty years-..........................................................................................................................203 P. P. G. SEDIRIS, vs M. S. ROSLIN In considering whether or not a presumption of ouster should be drawn by reason of long-continued possession alone of the property owned in common, it is relevant to consider the following, among other matters: (a) The income derived from the property. (b) The value of the property. (c) The relationship of the co-owners and where they reside in relation to the situation of the property. (d) Documents executed on the basis of exclusive owner ship. ......................................................................212 ANGELA FERNANDO VS. DEVADEEPTHI FERNANDO Partition Law, No. 21 of 1977, sections 2(1) and 25(1) -If land is not commonly owned is investigation of title necessary? - Ouster - Possession becoming adverse - Long continued possession by a co - owner? - Counter presumption of ouster. ........................................................................................................................................................233 LESLIN JAYASINGHE VS ILLANGARATNE - Sri Lanka Law Reports - 2006 - Volume 2 , Page No – 39 Partition Action-Evidence Ordinance, section 103-Burden of proof-Prescription 'Ordinance, No. 22 of 1871-section 3-Symbolic Possession-section 31, section 33,-Notaries Ordinance-t: Due Execution?-Notaries failure to observe his duties with regard to formalities 7- Registration of Documents Ordinance section 7-Prior Registration-Can it be raised in appeal 7- Mixed question of law and fact 7 - Co-ownersRights7-ouster vital..............................................................................244 PUNCHI MENIKE v. APPUHAMY et at. Diga marriage of daughter-Re-acquiring binna rights- Prescription among co-owners. A daughter married in diga can regain, even after her father's death, binna rights during the lifetime of her husband and without any divorce from him, or re- marriage in binna, by maintaining a close and constant connection with the mulgedara.There may be prescription among co-heirs where there is an overt act of ouster or something equivalent to ouster. But what might be acts of adverse possession against a stranger have, in questions arising between co-heirs, to be regarded from the standpoint of their common ownership. New Law Reports Volume 19, Page No 353 View - Volume 19....................................................................257 J. M. DON HANNY ALEXANDRA, vs Thomas Jayamanna Prescription-Co-owners-Family arrangement whereby property of deceased given to one of the heirs by the others-Oyster- Evidence of adverse possession thereafter by such heir-Acquisition of title by prescription........269 WICKREMARATNE AND ANOTHER v. ALPENIS PERERA Prescription among co-owners- Proof of ouster-Partition action. In a partition action for a lot of land claimed by the plaintiff to be a divided portion of a larger land, he must adduce proof that the co owner who originated the division and such co-owner's successors had prescribed to that divided portion by adverse possession for at least ten years from the date of ouster or something equivalent to ouster. Where such co-owner had himself executed deeds for undivided shares of the larger land after the year of the alleged dividing off it will militate against the plea of prescription. Possession of divided portions by different co-owners is in no way inconsistent with common possession. .....................................280

- 3. PIYADASAAND ANOTHER VS. BABANIS AND ANOTHER Partition Law, No. 21 of 1977 - Plea of Prescription - Co-owner prescribing to entire land?-Presumption of ouster - Essentials of a Kandyan Marriage - Special Law in derogation of the Common Law -Can a new point be raised for the first time in appeal?-Can there be a valid Kandyan marriage by way of habit and repute - Kandyan Marriage and Divorce Act, Section 3 - Presumption in favour of marriage under Roman Dutch Law - Evidence Ordinance, section 103. 2006 - Volume 2 , Page No - 17............................294

- 4. 1978-79 - Volume 2 , Page No - 166 Sri Lanka Law Reports - 166 - and another - COURT OF APPEAL. RANASINGHE, J. AND TAMBIAH, J. C. A. (S.C.) 237/73 (I) D. C. JAFFNA 539/p. MARCH 27, 30, 1979. PONNAMBALAM V. VAITIALINGAM CO OWNERS PARTITION ACTION CLAIM BY DEFENDANTS THAT CORPUS AMICABLY DIVIDED AND SO POSSESSED PRESCRIPTION PRINCIPLES APPLICABLE. Held The question whether a co owner has prescribed to a divided lot as against the other co owners is one of fact and is to be detonated by the circumstances of each case. The mere reference to undivided shares in deeds executed after the alleged date of division does not have the effect of restoring the common ownership of a land which has been dividedly possessed and where such divided portions have become distinct and separate entities. The learned trial Judge had in this case correctly found that the corpus had been divided and separately possessed to the exclusion of the other co owners for about 30 to 40 years prior to this action and accordingly dismissed the action holding that at the time of its institution the corpus was not owned in common. Cases referred to (1) Corea v. Iseris Appuhamy, (1911) 15 N.L.R. 65; 1 C.A.C. 30. (2) Tillekeratne v. Bastian, (1918) 21 N.L.R. 12 (F. B.). (3) Abdul Majeed v. Ummu Zaneera, (1959) 61 N.L.R. 361 ; 58 C.L.W. 17. (4) Hussaima v. Ummu Zaneera, (1961) 65 N.L.R. 125, 64 C.L.W.7 (5) Danton Obeysekera v. Endiris. (1962) 66 N.L.R. 457. (6) Simon Perera v. Jayatunga, (1967) 71 N.L.R. 338.

- 5. (2) Nonis v. Petha, (1969) 73 N.L.R. 1 ; 78 C.L.W. 33. (3) Jayaneris v. Somawathie, (1968) 76 N.L.R. 206. (9) Perera v. Kularatne, (1972) 76 N.L.R. 511. (10) Belin Nona v. Petara, (1972) 77 N.L.R. 270. (11) Hamidu Lebbe v. Ganitha, (1925) 27 N.L.R. 33; 6 C. L. Rec. 159: 3 Times L.R. 102. (12) Sideris v. Simon, (1945) 46 N.L.R. 273. (13) Mensi Nona v. Neimalhamy, (1927) 10 C. L. Rec. 159. (14) Girigoris Appuhamy v. Mary Nona, (1956) 60 N.L.R. 330. APPEAL from the District Court, Jaffna. C. Thiagalingam, Q.C., with V. Arulampalam, for the plaintiffs appel¬lants. C. Ranganathan, Q.C., with K. Sivanathan, for the 2 (a), (b) and (c) defendants respondents. Cur. adv. vult RANASINGHE, J. The plaintiffs appellants (hereinafter referred to as plaintiffs) who are husband and wife respectively instituted this action to have the land called and known as Ella Silum and other parcels, 20 Ims in extent and described in the schedule to the plaint partitioned as between the plaintiffs and the 1st to 3rd defendants. The contesting defendants, who are the 2a 2c, and the 3rd defendants appellants, have taken up the position that the corpus had been amicably divided over 60 years ago, and has ever since the said division been dividedly possessed and that it is now not commonly owned, and that, therefore, the plaintiffs' action Should be dismissed.

- 6. The learned trial judge has upheld the position taken up by the contesting defendants and has accordingly dismissed the plaintiffs' action. This appeal therefore raises once again the question of prescription among co owners, a question which has come up over and over again before our Courts and has received careful and exhaustive consideration both by the Supreme Court and by Their Lordships of the Privy Council. The co ownership of a land owned in common could be terminated broadly in one of two ways either through Court or out of Court. Common ownership could be brought to an end by an action instituted in Court for a partition in terms of the provisions of the Partition Act. The best evidence of such a termination would be the Final Decree entered by Court. Termination of common ownership without the intervention of court could be in one of two ways either with the express consent and the willing participation of all the co owners, or without such common consent. An amicable division with the common consent of all the co owners can take one of two forms: a division given effect to by the execution of a deed of partition or of cross conveyances which said notarial documents would then be the best evidence of such a termination or an internal division and the entry into separate possession of the divided allotments by the respective co owners to whom such lots were allotted at such division. In the case of a partition by court and an amicable division by the execution of the necessary deeds, the common ownership ends forthwith. In the case, however, of an internal divisions effected by the co-owners with the express common consent of them all, the common ownership does not in law come to an end immediately. In such a case common ownership would, in law, end only upon the effluxion of a period of at least ten years of undisturbed and interrupted separate possession of such divided portions. Proof of such termination will depend on evidence, direct and or circumstantial, and is a question of fact. The termination of common ownership without the express consent of all the co-owners could take place where one or more parties either a complete stranger or even one who is in

- 7. the pedigree¬ claim that they have prescribed to either the entirety or a specific portion of the common land. Such a termination could take place only on the basis of unbroken and uninterrupted adverse possession by such claimant or claimants for at least a period of ten years. Here too proof of such termination would be a question of fact depending on evidence, direct and or circumstantial. I shall, before I proceed to deal with the facts and circumstances of the case, set down the relevant principles of law which are applicable to a case such as this. Any discussion of the principles relating to prescription among co owners must necessarily commence with the judgment of Their Lordships of the Privy Council, delivered in 1911 in the case of Corea v. Iseris Appuhamy (1)where it was clearly and authoritatively laid down: that a co owner's possession is in law the possession of other co owners : that every co owner is pre¬sumed to be possessing in such capacity : that it is not possible for such a co owner to put an end to such possession by a secret intention in his mind: that nothing short of ouster or something equivalent to ouster could bring about that result, Thereafter in the year 1918, in the case of Tillekeratne v. Bastian (2) a Full Bench of the Supreme Court was called upon to apply the principles laid down in Corea v. Iseris Appuhamy (supra) and con¬sider, inter alia, the meaning of the English law principle of a "presumption of ouster ", and it was held: that it is open to the Court, from lapse of time in conjunction with the circumstances of the case, to presume that a possession originally that of a co¬-owner has since become adverse : that it is a question of fact, whenever long continued exclusive possession by one co owner is proved to have existed, whether it is not just and reasonable in all the circumstances of the case that the parties should be treated as though it had been proved that that separate and ex¬clusive possession had become adverse at some date more than ten years before the institution of the action. Thereafter the, question has been considered over and over again by the Supreme Court, and in the year 1959, in the case of Abdul Majeed v. Umma Zaneera (3) in a very lucid and exhaustive

- 8. discussion of the principles relating to prescription among co owners and the presumption of ouster, which had been laid down up to that point of time by both the Privy Council and the Supreme Court con¬cluded : that the inference of ouster could only be drawn in favour of a co owner upon proof of circumstances additional to mere long possession : that proof of such additional circumstances has been regarded in our Courts as a sine qua non where a co-owner sought to invoke the presumption of ouster. This case thereafter went up in appeal to the Privy Council, and the Judg¬ment of the Privy Councli is reported (4). Although their Lordships regretted having to advise Her Majesty to dismiss the appeal, Their Lordships were nevertheless content to accept the relevant principles of law, as expounded by the Supreme Court. I shall now refer to the judgments reported after the judgment (4) referred to above which have dealt with the question. In the case of Danton Obeysekera v. Endiris (5), Sansoni, J. held that where an outsider bought a 2/3 share, about two roods in extent of a co owned property, from two co owners and sepa¬rated off such portion, not as a temporary arrangement for conveniences of possession, but more likely as a permanent mode of possession, and possessed it for over twenty years, the lot so separated off ceased, with the lapse of time and exclusive pos-session, to be held in common with the rest of the land, and that those who so possessed it were entitled to claim that they have prescribed to it. This decision does not, in my opinion, in any way offend against the principle referred to by (H. N. G.) Fernando, J. The additional circumstance that was required was supplied by the 1st defendant's prosecution of the 2nd defen¬dant for destroying the barbed wire fence which had, been erected to separate off the portion which was then being sepa¬rately possessed by the 1st defendant. The subsequent Judgments of Siva Supramaniam, J. in Simon Perera v. Jayatunga (6) at p. 431 of the Privy Council in the case of Nonis v. Peththa (7), of Weeramantry, J. in Jayaneris v. Somawathie (8), of Pathirana, J. in Perera v. Kularatne,(9), and of H. N. G. Fernando, C.J. in Belin Nona v. Petara (10),

- 9. which have also dealt with the question of prescription among co owners, have not expressed any views which in any way, tend to deviate from the principles made explicit in the judgments of the Supreme Court in the case of Abdul Majeed v. Ummu Zaneera (supra) and approved by the Privy Council. It has also been laid down that the question whether a co- owner has prescribed to a particular divided lot as against the other co owner is one of fact and has to be determined by the circumstances of each case (2). (11.), (12), (3), (5), (6) at p. 343. It is also now settled law that the mere reference to undivided shares in deeds executed after the alleged date of division does not have the effect of restoring the common owner¬ship of a land which has been dividedly possessed and where such divided Portions have become distinct and separate entities (13), (14) at p. 332; (6) at 343. The principles applicable are, therefore, quite clear and unambiguous and have been authoritatively laid down ; but, as it very often happens, the real difficulty arises only in their application to the facts and circumstances which are established in a particular case. I shall now proceed to consider whether, having regard to the principles set out above, the learned trial judge's finding that the corpus sought to be partitioned had been amicably divided and, had been dividedly possessed for a long period of time prior to the commencement of the proceedings and that the corpus had, therefore ceased to be owned in common at the time the plaintiff instituted this action. As already stated, the position of the contesting defendants in this case is that the amicable division had taken place about 60 years ago. No witness is available to them to give direct evidence with regard to the said division which the contesting defendants claim had taken place. They, therefore, rely on circumstantial evidence to establish their claim. The learned trial judge hag found that the parties, who are said to be entitled to interests in the corpus, have in fact been separately possessing the several lots depicted in the Plan X : that the said parties have so possessed the several lots dividedly to the exclusion of the other co owners ; that such exclusive possession has gone on for about 30 40 years prier to

- 10. the institu¬tion of this action ; that the fences separating the various lots are very old live. fences; that the said fences are boundary fences and not " screen fences ". These findings of the learned trial judge are supported by the evidence placed before him at the trial and there does not seem to be any good reason to interfere with the said findings of the learned trial judge. It is also clear that lot, 7 on which the well stands has been separately fenced in, and that access has been Provided to this lot from all the other lots 2, 4, 8. 10 and 11 along well defined path ways. The learned trial judge has also found that, prior to the dis¬pute raised by the plaintiff, shortly before the commencement of these proceedings, to the construction of a kitchen by the contesting defendants on lot 4, substantial buildings had been put up by the contesting defendants on lot 4 without any protest from the plaintiffs. The 1st defendant has also thereafter constructed a building on lot 4. The 1st plaintiff who has been in possession of lot 2 stated that he himself has built a house on lot .2, and that before that house was constructed by him, there was on that same lot an old house in which his grandmother and also his parents had resided. It also transpired in evidence that the 1st defendant, who is said to have been allotted lot 11, had removed the southern boundary fence of lot 11 and amalgamated lot 11 in Plan X with lot 12, which is a portion of the land lying to the south of lot 11 and which also belongs to the 1st defendant. The learned trial judge has stated that, when the 1st defendant carried out such amalgamation, there had been no protest from the plain¬tiffs and that such silence on the part of the plaintiffs was because they, considered lot 11 to be the exclusive property of the 1st defendant. The deeds P2 of 1917, 1 13 and P4 both of 1935, and P5 executed only a few days before the plaintiff came in to court in June, 1961, deal with undivided shares in the corpus. Whilst P2 has been executed as far back as 1917 which is the year in which the amicable division referred to by the contesting defendants is said to have taken place, P3, which has been executed in 1935 is in the chain of title" of those who have

- 11. been in posses¬sion of lot 11 which, as already stated, had been separately possessed by the 1st defendant. Even though evidence was placed on behalf of the plaintiffs that other co owners too had ,exercised acts of possession over lot 11, such evidence has not been accepted by the learned trial judge. The deed P4, like P5 referred to above, figure in the Pedigree of those who have been in possession of lot 2. The learned trial judge has taken the view that the references to undivided shares in these deeds do not militate against the position put forward by the contest¬ing defendants, and that such descriptions have been made not with reference to the actual mode of possession but as a result of the notaries merely following the descriptions in the earlier title deeds. Having regard to the circumstances of this case, I do not think that the view taken by the learned trial judge could be said to be untenable. The additional circumstances which, according to the principles referred, to earlier, is required in a case of this nature has also, in my opinion, been established in this case by the contesting defendants. The contesting defendants produced marked 2D1 a certified copy of a complaint made by the 1st plaintiff in this case, on 21.2.1958, against the deceased 2nd defendant to the Rural Court of Chankani, in Case No. RC/C/CRM 1054, that the said 2nd defendant has failed and neglected to fence the southern boundary fence of the 1st plaintiff's dwelling land, in breach of Rule 46 of the Village Committee Rules of 3.2.1928, and the said 2nd defendant has therefore committed an offence punishable under section 26 (1) Rural Courts Ordinance 12 of 1945. According to an entry dated 25.3.1958, appearing on the face of the said document Dl itself, the 1st plaintiff had thereafter informed court, that, as the said 2nd defendant had erected the fence, he was withdrawing the case ; and that the 2nd defendant has then been discharged. According to the Plan 'X' the lot possessed by the 1st plaintiff and on which he resides, is lot 2, and to the south of lot 2 is lot 4 which was possessed by the said 2nd defendant. The southern boundary of the 1st plaintiff's dwelling land would, therefore, be the boundary between lots 2 and 4 in Plan 'X'. The 1st plaintiff, on being questioned with regard to the said case, admitted having filled it but denied that he described the fence in question as a

- 12. " boundary fence ". His position is that he himself called it a "screen fence" but that the Chief Clerk, who had written out the complaint (the original of 2Dl) had described it as a " boundary fence " without his authority. The learned trial judge has disbelieved the 1st plaintiff's evidence on this point. The 1st plaintiffs description of the fence which had been erected to separate lot 2 from lot 4 in Plan X, shows that these lots have been so separated off " not as a temporary arrange¬ment for convenience of possession but more likely as a permanent mode of possession ". As already stated, once the said 2nd defendant re erected the fence in question, the 1st plaintiff had withdrawn the case. It appears to me that the 1st plaintiff's acts as embodied , 2D1, gives a clear indication of the nature and the character of the possession of the various lots, depicted in Plan 'X' by the respective co owners. On a consideration of these facts and circumstances, I am of opinion that the learned trial judge's finding that the corpus was not, at the time of the institution of this action, owned in common is correct and should be affirmed. The appeal of the plaintiff s' appellants is accordingly dismissed with costs. TAMBIAH, J. I agree. Appeal dismissed. New Law Reports Volume 15, Page No 65 New Law Reports D.C. Chilaw, 3,934. [PRIVY COUNCIL.]

- 13. Present: Lord MacNaghten, Lord Mersey, and Lord Robson. COREA v. APPUHAMY et al.Prescription-Possession by one co-heir enures to the benefit of the other co-heirs- Adverse possession. Possession by a co-heir ensures to the benefit of his co-heirs. A co-owner's possession is in law the possession of his co- owners. It is not possible for him to put an end to that possession by any secret intention in his mind. Nothing short of ouster or some thing equivalent to ouster could bring about that result. The whole law of limitation is now contained in Ordinance No. 22 of 1871. THE facts of this case are fully set out in the judgment of the learned District Judge (T. W. Roberts, Esq.): - The plaintiff in the present action seeks a partition of the fifteen lands mentioned in the schedule attached to his plaint on the strength of his purchase in 1907 of two-thirds share thereof from Balahami and her two nieces, Allina and Nonnohami. The plaintiff and his vendors say that they were at the date of transfer under the impression that Balahami had married after the Matrimonial Ordinance, and that her children had not on their father's death become entitled to any part of Balahami's share. It subsequently turned out, however, that Balahami's marriage was dated before 1876, and was in community of property. So her two children have intervened, and claimed each one-third part of one-half of the share to which Balahami was entitled. Their claim is admitted by the plaintiff. In another point, too, the facts stated in the plaint are not accurate. Therein all fifteen lands are asserted to have formed part of the estate of one Elias, and so on his death to have devolved in part on his sister Balahami and nieces and nephews above mentioned. It was asserted, however, at the trial that certain of these lands never formed part of Elias's estate, and plaintiff thereupon disclaimed title to such of those lands as, may appear on the title deeds to have been bought

- 14. originally in the name, not of Elias, but of first defendant, Iseris. The lands in question form a large and valuable estate of over one hundred acres, mostly now in full bearing. The title deeds thereto, on which both the contesting parties rely, convey title to one Elias. Elias died in 1878. Since that date all the lands have been in the occupation of the contesting defendant, Iseris, the brother of Elias. The plaintiff's vendors allege title by inheritance from Elias. They say that Elias was a man from Baddegama, which is situated in the Galle District, 120 miles distance from Chilaw; that he migrated, and made a large fortune in Chilaw District and died here. Their case is that Elias was one of a numerous family, and had one brother, the first defendant. Iseris, and three sisters, Babahami, Balahami, and Sinnatcho, Babahami, according to the plaint, died childless. Balahami married, had three children (the intervenients) by her first husband, and another child, a bastard, by her second consort. She is still alive. Sinnatcho died in Galle District, leaving two daughters, Allina and Nonno. The plaintiff led evidence to show that after the death of Elias Balahami came to Chilaw District with her children and her second consort to seek her patrimony on receipt of news that Elias had died and left a big estate; that some years thereafter Sinnatcho's husband and children also migrated to this district; and that both have thereafter allowed first defendant, Iseris, as the chief male member of their family, to manage and possess their estate. They say that during the thirty years since their migration the first defendant, Iseris, had up to 1907 all along acknowledged their title as his co-heirs, and made them continual advances of money and provisions pending final settlement of the estate. They allege that Iseris deceived them into the belief that he had taken out administration, and had to pay all debts before the property could be divided among the heirs. To all this Iseris gives a total denial. He says that he was partner with Elias, and that on Elias's death he took possession of the estate as his own, and has all along possessed it as such. He denies the allegations as to his kinship with plaintiff's

- 15. vendors, and says they are his cousins. During his de facto possession for thirty years he has planted and leased, mortgaged, and sold various of the lands, and generally dealt with them as owner. He has, he says, been frequently liberal to his cousins, and allowed Balahami to live on one of the lands in question. But he denies that he thereby acknowledged their title, and says that what he did was simply matter of charity. The issues as to the pedigree and as to Iseris's alleged partnership with Elias need not detain us long. As to the pedigree, there is a considerable resemblance in physiognomy between Iseris and Balahami; and two witnesses from Baddegama, of a goodly age, have testified that the plaintiff's account of the pedigree is the truth. Their depositions, it is true, displayed a wonderful accuracy of memory in regard to the names of many members of Elias's family. Such accuracy in nomenclature could, in Sinhalese village folk, only be the result of careful preparation. But the drilling required to produce that exactitude may have been their own effort. My impression, on the whole, was that these two were honest witnesses, and their statement is confirmed by facial resemblance above noted. I should have accepted that evidence, even if it had stood alone. As it is, the plaintiff has also filed a number of ola extracts of registration, which conclusively prove the pedigree of his vendors. I accordingly find for plaintiff on issues 4, 5, 6, and 8. Similarly, I have no hesitation in finding for plaintiff on issue 10. The only proof that the title deeds, which stand in the name of Elias represent purchases with partnership money, consists in the ipse dixit of Iseris. Now, Iseris's evidence is deeply interested, and worthless on that ground alone. Moreover, Iseris is a convicted forger and thief. And his deposition in the present case directly and categorically contradicts on every possible point the evidence which he gave in D. C. Chilaw, No. 3,855. On the mere statement of such a witness, expert not only in crime and incarceration, but also in perjury, I am not prepared to find any fact proved in the absence of their corroboration aliunde. On the contrary, I shall take steps to prosecute him for his perjury.

- 16. There remains the crux of the case the question of prescription. Iseris has admittedly had de facto possession for practically thirty years, and it has to be decided whether that was precarious possession or possession on an adverse and independent title. The law on this point was exhaustively discussed by the plaintiff's proctor, but I find myself unable to agree with much of his argument, endita as it was. He argued, firstly-and this much, it seems to me, was clearly sound-that no length of precarious possession, even if unaccompanied by payment of rent or other such acknowledgment, can found a valid prescriptive, title. Further, non-enjoyment, for however long continued, will not by itself destroy title to property precariously possessed by another. To that extent it is manifest that the finding of the Privy Council in Nagudu Marikar v. Mohamadu 1 has over-ruled the decision reported at Vanderstraaten 44. But the plaintiff's argument went further. Mr. C. A. Corea contended also that on the over-ruling of the decision reported in Vanderstraaten 44 the law reverted to its condition as it stood under the more ancient decision to be found in Morgan's Digest 21 and 273. Now, this is clearly not the fact. While the Privy Council in Nagudu Marikar v. Mohamadu did in fact over-rule any previous decisions in so far as they may have held that a precarious possession may give a prescriptive title, it over- ruled nothing else, and nowhere has ruled that the law of prescription is now the law laid down in the judgment in Morgan's Digest, at page 273. If the two decisions be examined, it will be found that they are profoundly at variance. What was held in Nagudu Marikar v. Mohamadu was that not even centuries of precarious possession will found a valid prescriptive title. Whereas in the decision reported in Morgan's Digest, it is clearly implied that thirty years precarious possession will found and create a valid title. The two decisions are therefore directly at variance on that point, and it is a contradiction in terms to say that the later re-establishes the earlier. Again, it is now settled law that since the Ordinance of 1871 the Roman-Dutch law of prescription has been superseded

- 17. (vide l N. L. R. 200). This was a decision of the Full Court, and there are others. There is nothing inNagudu Marikar v. Mohamadu which over-rules this. But with this view of the law it is impossible to reconcile the decision reported in Morgan's Digest. The latter supports and defends the Roman-Dutch law, the common law as it stood. Among other things, it decides that a precarious possessor, in order to obtain a good title by prescription, must transform the character of his possession, not merely into an adverse possession, but into an adverse possession based on a bona fide title. It also recognizes the distinctions between prescription longi andlongissum temporis. But our present law recognizes none of these distinctions. Under the decision reported at lN. L. R. 200 and under many others and clearly under the words of the statute, it matters 1 (1903) 7 N. L. R. 91. not whether the prescriptive possession commences with a bona fide title or otherwise. What is required, and all that is required, is that there should be proof of ten years' unbroken possession, or an adverse and independent title. It makes no difference whether the title be just or unjust. It is necessary only that it should be adverse and independent. To interpret the word " title " in the statute as meaning only a Justus titulus is unwarrantably to import in to it a meaning which is not there. It is as if one were to agree that the abstract word " colour " does not mean any colour but only blue, or the word " triangle " refers only to the isosceles and not to the scalene variety. The law is, therefore, that one coheir, so long as he possesses the property precariously on a derivative or dependent title (which involves acknowledgment of the title of the other co- heirs), cannot by such possession prescribe against his co- heirs. It is not true that he can never, under any circumstances, prescribe against them. If he sets up an adverse title, and by overt acts to the knowledge of his co- heirs defies their title and disclaims the precarious character of his possession, and thereafter has the uninterrupted possession on such adverse title for ten years without payment of rent or other acknowledgment of their collateral title, he will thereby acquire a good prescriptive title. To hold otherwise would be to

- 18. encourage the careless in his lack of care and the fool in his folly, it would enable indolent co-parceners to rely on their own laches and oust innocent purchasers for value of apparently good prescriptive titles. The numbers of such purchasers are great in Ceylon, and the view of the law which Mr. Corea advocated would amount to a social revolution. The burden, therefore, lay on plaintiff to prove that Iseris's possession began or went on in a precarious or permissive character. If he did so he would shift the burden on to Iseris, who would have to prove how and when he converted this dependent character of his title into one of independence. I have come to the conclusion that plaintiff has wholly failed to prove that Iseris's possession either began or went on in a precarious character. He has equally failed to account for a long series of overt acts ut dominus on Iseris's part, which would long ago have transformed the character of his possession from precarious to adverse, if it had ever stood in need of such change. I have summarized above the explanation which the plaintiff's vendors gave of the long occupation by Iseris. When we come to consider the proof of that story, its paucity and weakness are strikingly apparent. Practically the only proof that Iseris possessed, not as owner but as agent for his co-heirs, consists of the evidence of those co-heirs. Their word deserves little credence. They are persons neither of worth nor position. They stand to win or lose on this litigation a large sum, in each case running into over Rs. 1,000. With so large a stake involved, it is certain that persons of their sort and position will depose to almost any falsehood. But I consider at length their counsel's argument on the facts, because the property involved is very large. Mr. Corea appears to have recognized that his evidence on the matter of possession was slender, and attempted by his argument to show that the evidence for plaintiff was supported by the balance of probability. He set out, in the first place, to prove that Iseris had, on his brother's death, taken out administration, and then got the record of administration proceedings destroyed to cover up his track. Now, the record is lost, and Iseris has, by document D 37, clearly demonstrated that ha complained to His Excellency the Governor of its loss

- 19. and of other matter, and that on his complaint thirty years ago a record keeper of this Court was dismissed. If Iseris had wished to destroy it, and had got it destroyed, why should he complain of its loss? And why should the Government of Ceylon have on that complaint dismissed the record-keeper? These facts are irreconcilable with the suggestion that Iseris procured its destruction. That suggestion is evidently the merest verbiage. The proof of administration having been taken out by Iseris is defective, and consists chiefly of a dubitant recollection of Mr. Cooke's, of the general belief in and around Galmuruwa, and of hearsay. It seems to me that the proof of that has failed, and so I find on that issue. The argument of plaintiff's proctor was to the following effect. Migrations of Sinhalese to distant districts are rare, and never made without good reason. The only reason why Balahami and her nieces could have come to this district, he contended, was that they were seeking their share of Elias's large estate. Having so come, they would, he urged, be sure to demand that share and did so demand it. If Iseris had then refused, litigation would have been, it was argued, sure to have begun at once. Therefore, Iseris must, as they say, have admitted their claim, and entered on and thereafter continued his possession in the dependent title of manager for his female relatives. Thereafter, it was natural, and in accord with Sinhalese customs, that they should allow him to manage as he pleased, as it was not inconsistent with his position that he should give out the lands on planting agreements; and leases, and mortgage them to meet expenses. His sales were matter which they did not know or understand to be sales of their shares. It will be seen at once that this agreement begins with a daring petitio principii, and continues along a road liberally paved with examples of the fallacy of non sequitur. In the first place, it is not true that the only reason why Balahami and then Sinnatcho's children should have migrated was that they came to demand share of Elias's estate. Any number of equally natural reasons are possible and conceivable. It may have been that Balahami found her own village uncomfortable after her illicit relations with her second consort. It may have been, and this was probably the case,

- 20. that they migrated in the simple hope of charity or employment. With kinsfolk at the end of the journey, such migrations are not in the least uncommon, because the people of Ceylon invariably show the most admirable liberty to any of their kinsfolk, at least any with whom they have not quarrelled. The assertion that the object of their migration must have been to demand a share of their dead brother's estate was the coping stone of the whole argument. That assertion is not fact, and consequently the whole argument crambles away. Not only is it not true, there is on the record proof of facts which clearly and firmly negative that suggestion. It is admitted that Sinnatcho's children did not migrate till some years after Balahami. But if the reason for migration had been to enter on the estate of Elias, which they say had devolved on them, it would have been most natural that they should migrate simultaneously, or at any rate in quick succession one after the other. Again, it appears from the admission of plaintiff's own witness that Elias's other sister, Babahami, did not die childless, as the plaint avers she did. She left four children at her death. Neither she nor her children, however, have ever migrated. Now, if the statement of Balahami had been true, and if on the death of Elias Iseris had apprised his kinsfolk in Baddegama of that death, and their consequent title to Elias's estate, we may be sure, with the same certainty with which we know that 2 plus 2 makes 4, that Balahami and the family would not have left that fortune, which awaited them, to go a begging. It is, therefore, beyond doubt that Balahami's evidence as to the object of her migration is totally false. In the next place, it is clear, since Iseris is not shown to have been administrator, that at the date of his entry on Elias's estate he did not ask, nor need to ask, the consent of his sisters. Elias died in 1878. Iseris came out of jail at the end of that year, or in 1879. Balahami, if we accept her own evidence as given in 3,855, migrated five years after her father died, and she was thirty or thirty-five years old when her father died. She wag born in 1850. It follows that she was about thirty-five when she migrated, and that fixes the date of migration at 1885, but almost certainly not earlier. Therefore, Iseris had

- 21. had seven years' possession before Balahami appeared on the scene. In the third place, supposing for the sake of argument that the object of her migration was to claim share of Elias's estate, and that she did so claim it does not in the least follow that Iseris admitted her claim. She was a new arrival, and poor. Iseris was a criminal, and had in his possession the title deeds. Looking at his unsavoury past, it is infinitely more probable that he did not admit her claim. His interest in the law as to co- heirs was probably slight. It is far more natural to suppose that his entry on the estate of Elias and his continuance therein was based on nothing else than the ancient doctrine that he should take who can, and he should keep who has the power. That being so, supposing Balahami had demanded share of the estate and Iseris had refused, it is not clear why litigation should follow. He had seven years' possession behind him. He had the title deeds. He had the money. Balahami had nothing; what is more likely than that she accepted his bounty and dropped her claim? She would buy her claim in those circumstances? How could she fight the claim herself? That is a double non sequitur,then, when it was argued that Balahami must have demanded her share of the estate and must have got it. These things were neither necessary nor probable. Continuing further, the extraordinary temerity of the argument and evidence for plaintiff reveals itself yet more glaringly. According to Balahami-and the remark applies, mutalis mutandis, to her nieces-she owned one-third share of the estate, and Iseris admitted that. On Iseris's estimate in his deed of gift the property is worth Rs. 70,000. On Balahami's statement, of the value, Rs. 80,000 thirty years ago. According to her present estimate of the crop (100,000 coconuts at a plucking), it yields an income of Rs. 24,000 per annum, and must be worth Rs. 240,000. Much of it has been in bearing for many years. At the lowest estimate her share of the income for the last twenty years ought to have been Rs. 3,000 per annum. Nevertheless, she comes into Court in the garb of poverty. She has admittedly remained poor, while Iseris has been rich. She has given her sons and nieces in marriage without portions. She has lived on Rs. 200 per annum, though the income should

- 22. have been Rs. 3,000, and had never complained about it. One of the husbands of her nieces said that he used to come and get Rs. 50 or Rs. 60 every other month from Iseris. Yet he, too, showed no signs of wealth. On his statement of income and expenditure he ought to have now in his possession Rs. 3,000 or Rs. 500 cash. He has not got it, and says he spent it on vedaralas. To do so would take him over a century, I have no doubt that his statement was false. Finally, Balahami and the rest wish me to believe that for thirty years they have believed Iseris's statement that he was still administering the estate, though they received no notices as heirs, and that they never suspected his intentions during that long period, though he has leased and mortgaged the lands, Sinhalese villagers may be ignorant, but they are not stupid in this degree. The whole story, as the vendors to plaintiff told it, appears to me be not only improbable, but hopelessly incredible. I am of opinion that Iseris's possession began and went on in defiance. He ejected the official receivers, and he ejected the mistress of Elias. He continued in a long series of overt acts, of which Balahami and his nieces were probably well aware, to lease, mortgage, sell, and plant, and otherwise dispose of the property as its sole owner. As he had entered in the character of sole heir or plunderer, whichever it was, so he continued, and acknowledged no title in any one else. He has acquired a good prescriptive title. The plaintiff's case must therefore fail, even if considered only as an action in rei vindicatione. As an action for partition it would fail even if his case had been true, because on his witnesses evidence certain of the co-heirs, viz., Babahami's descendants. remain unjoined , and because, doubtless, in the long list of lands, many of which plaintiff and his witnesses admittedly know little or nothing about, there are doubtless some to which other strangers have or claim title; as, for instance some of the persons who have planted them up. Plaintiff has not proved a title as against the world, even if all the witnesses evidence is true. I have to discuss yet another point. Plaintiff's purchase was criticized (1) as a speculative purchase, (2) as unprofessional conduct and dishonourable conduct. With the first criticism I

- 23. agree. The deed recites a consideration of Rs. 18,000 as received before its execution. In fact, plaintiff and his vendors admit that the whole has not yet been paid. Up to date the vendors have received about Rs. 8,000, partly and mostly in cash, and partly in rice, kurakkan, legal advice, and such curious though valuable equivalents of the solid rupee. For the payment of the unpaid balance the vendors obtained no security. The plaintiff was aware that his purchase was of a disputed title, and that he could not lay his grasp on what he bought except by process of expensive litigation. Certainly it was a speculative purchase. It does not follow that it was dishonest, and Mr. Bawa in arguing at one and the same time that the purchase was a speculative purchase of a bad title, and also that the purchaser behaved unprofessionally in taking from his clients credit for the large unpaid balance, clearly fell into the fallacy known to the schoolmen under the name of circulus in arguendo. If the purchase was a speculative purchase of a bad title, the vendors have lost nothing, but gained considerably at the expense of their legal adviser. In that there was no dishonour. They, i.e., the vendors, confirm plaintiff's statement that he has paid them Rs. 8.000 of the consideration, and they make no complaint against him. It was argued that plaintiff's statement as to payment should be disbelieved. Reference was made to his vivacious past in the matter of litigation and to his cases with the present defendant. While, however, it is true that plaintiff is addicted to the habit of buying disputed titles, and has consequently been involved in plenty of litigation, both criminal and civil, he has never been found to have done anything dishonest or dishonourable. The criticism directed against him in the Privy Council decision in Corea v. Pieris1 bore reference to a case wrongly laid in Chilaw Court, but was based on a misapprehension of fact. And what is most material of all the defendant in the present case ought easily to have been able to show, if he seriously thought so. that the plaintiff has not paid Rs. 8,000 to his vendors. If in fact he* has not paid that sum, his vendors doubtless have not got it in their possession, and would probably have been unable to explain where it has gone to if they had been cross-examined on that point. They were not so cross-examined, and I conclude that

- 24. defendant did not at all firmly believe that that sum had not been paid. Anyway, the plaintiff is an advocate of this Court and a gentleman of wealth and position. His demeanour in the witness box was perfectly honest. Nor do I see any good reason, either in this case or in his some what lively and litigous past, why I should believe him to be anything but an entirely truthful witness. I cannot then agree that he has swindled his clients, or sought to deal with them improperly in omitting to secure them the unpaid balance of the consideration in the deed. He admits he owes that still. If he had denied it his conduct would have been unprofessional. If theirs had been a good title, the same criticism may perhaps have applied. In fact, it was a bad title; and his clients have gained Rs. 8,000 at his expense. It is certainly a matter of surprise that an advocate should indulge in such purchases of disputed titles. Such is not, I am sure, the ideal; nor, as I believe, or rather hope, the practice of his profession. But at the same time it does not appear that plaintiff had done anything dishonourable. For the reasons given above, the plaintiff's action must be dismissed with costs. I refrain from making an order that he should pay double costs, because, while I am anxious to discourage gambling in purchase of title to land and the application of the Partition Ordinance to such, the plaintiff has suffered enough in his loss or damage of loss of Rs. 8,000. Plaintiff appealed. H. A. Jayewardene (with him Chitty), for the appellant. Bawa (with him Wadsworth), for the respondent. The following judgment was delivered by the Supreme Court: - May 26, 1910. HUTCHINSON C.J.- This action was brought for partition of certain lands which the plaintiff alleged had been the property of Elias Appuhamy, who died unmarried and intestate in 1878 possessed of the said lands; and the plaintiff claimed an undivided share by purchase from some of the heirs of Elias. The first defendant, Iseris, denied the plaintiff's

- 25. 1 (1909) 12 N. L. R. 147. claim; he alleged that some of the lands were bought in the name of Elias with the money of Iseris and Elias. and that others of them were partly bought in the name of Elias with the money of Iseris and Elias, and partly bought by Iseris after Elias's death; and he said that on the death of Elias he, as Elias's sole heir, entered into possession of all the lands, and has been in undisturbed and uninterrupted possession of them for ten years by a title adverse to and independent of the plaintiff and all others. The District Court held that Iseris had acquired a title by prescription, and dismissed the action. The contest is as to whether Iseris has proved his prescriptive title. The appellant contends that the District Judge went wrong in thinking that, when it was once proved that Iseris had had de facto possession for more than ten years, the burden lay on the plaintiff to prove that Iseris's possession began or went on in a " precarious " or permissive character; he contends that if the Judge had not made that mistake, he might have come to a different conclusion upon the evidence; and that the evidence raises in fact a presumption that Iseris took possession as one of the heirs, and not as sole heir, and that that presumption had not been rebutted. The remarks of the learned Judge about the burden of proof were mistaken. The burden lay on Iseris that he had such possession as is explained in section 3 of Ordinance No. 22 of 1871. But the Judge finds that Iseris's possession "began and went on in defiance"; that he acted from the time of his first entry in 1879 onwards as sole owner; and that "as he had entered in the character of sole heir or plunderer, whichever it was, so he continued, and acknowledged no title in any one else. He finds that Iseris had had at least seven years' possession before Balahami, the first of the alleged coheirs, appeared on the scene; he thinks it beyond doubt that Balahami's statement that she went there in order to claim her share is totally false; and that even if she did make a claim, it is infinitely more probable that Iseris did not admit it. It appears, therefore, that he was clearly of opinion that Iseris had proved such possession as section 3 required by a title

- 26. adverse to that of the plaintiff and of those through whom the plaintiff claims; and that his opinion as to the burden of proof had no effect on his finding, for he finds that the evidence establishes that Iseris had proved that which he had to prove. With what intention did Iseris take possession on Elias's death? Did he mean to take possession as sole owner (whether as sole heir or otherwise), or only as one of the heirs? That is a question of fact on which I think that, upon the evidence, the Judge might fairly find as he did. Then, was his possession unaccompanied by any act from which an acknowledgement of a right in any other person would fairly and naturally be inferred? That is again a question of fact, and I think that again the finding of the District Court on it was supported by the evidence. I think that the appeal should be dismissed with costs. VAN LANGENBERG A.J.- This is an action brought under the Partition Ordinance. The plaintiff, claiming to be entitled to two-thirds of certain lauds, allots the remaining one-third to the first defendant. According to the title deeds the lands belonged to one Elias, who was born in the Southern Province, and migrated many years ago, when a young man, to the Chilaw District, where he traded successfully and amassed wealth. He died on July 23, 1878, leaving, according to the plaintiff, three sisters, Babahami, Sinnatcho, and Balahami, and one brother, the defendant, as his heirs. The plaintiff says that about twenty years ago Babahami died without leaving issue, and that Sinnatcho died about 1899 leaving two children. Allina and Nonno. By deed No. 1,181 dated December 5, 1907, the plaintiff acquired the right of Allina, Nonno, and Balahami. The first defendant claimed the whole land by prescription, and stated he had conveyed the lands in question to his son and the second defendant, reserving a life interest for himself. The second defendant was accordingly made a party in this action? The intervenients are the three children of Balahami. They say that their mother was married in community of property to

- 27. their father Ovinis Appu, who had died prior to the execution of the deed in favour of the plaintiffs, and that therefore their mother could not convey more than one-sixth. They claim the remaining one-sixth for themselves. It has been proved that Babahami had married and left children, all of whom, it is said, are now dead. Who their legal representatives are has not been ascertained and there is nobody in this case to represent them. Further, it has been established that Elias lived with a woman called Kittoria, who claimed to be his wife.; she is no party to this action. I think our judgment should bind only those who are parties to this case. I accepted the learned Judge's finding as regards the pedigree. The first defendant states that he joined his brother Elias and traded with him in partnership but the lands which were bought with the profits of the partnership were purchased in the name of Elias alone; that when Elias died he was in jail, and when he came out soon afterwards he found two headmen in possession; that he turned them out and entered into possession himself and remained in possession ever since; and that he had dealt with the property for over thirty years as his own. Plaintiff, on the other hand, asserts that Balahami and her children and Sinnatcho's children left their village on hearing of the death of Elias and came to first defendant, who acknowledged their rights to share the inheritance from Elias by giving them from time to time sums of money, and by allowing Balahami to live on Medawatta, a land which formed part of that estate. First defendant, however, says that whatever he did for his sisters and nephews 75 and nieces be did it out of charity, and that us a matter of fact not one of them ever asserted title to any portion of Elias's estate. The learned Judge has gone very fully into the facts, and it is enough for me to say that I agree with his conclusion, that whatever may have been the first defendant's reasons for doing so, the first defendant at the earliest possible moment, i.e., directly he came out of jail, took possession of Elias's property on his own behalf and for his own benefit, and that he

- 28. has done nothing since showing that he has acknowledged a right in anybody else. The Judge points out that for seven years not one of the family raised any questions as regards the first defendant's right to possession, and he does not accept the evidence led to show that first defendant in any way altered his position after the other members of the family appeared on the scene. Under our law there can be no doubt that one co-owner can acquire a prescriptive title as against his co-owners, though our Courts insist on strict proof of adverse possession. On the facts as found by the learned Judge, is the plaintiff in law entitled to a declaration that he has acquired prescriptive titles as against his co-owners? I understood Mr. Jayewardene to say, in answer to a question from me, that his contention was that when the owner of undivided share of land entered into the possession of the entirety, he must be presumed in law to have entered on behalf of himself and his co-owners, and that the onus was on him to show the starting of an adverse possession against them by proof of some overt act. I asked for some authority in support of this contention, but was referred to none. In the absence of any authority, I am unable to say that the contention is sound. It seems to me that the facts in each case must be considered before it can be inferred that one co-owner is in possession as agent of another. In this case, holding, as I do, that the first defendant entered in his own right and for his own benefit, I find that his possession became adverse at once, and continued so up to the date of the action. I would dismiss the appeal with costs. December 14, 1911. Delivered by LORD MACNAGHTEN: - This seems to be a very plain case. The action out of which the appeal has arisen was an action for partition of certain lands, part of the estate of one Elias Appuhamy of Galmuruwa, in the District of Chilaw. Elias died in July, 1878. He was never married, and he died intestate. His heirs were his brother Iseris and three sisters.

- 29. Taking by descent the heirs took as tenants in common in accordance with the provisions of section 18 of the Partition Ordinance of 1863. 76 Elias came originally from Baddegama, in Galle District, about 120 miles from Chilaw. His father and mother and the rest of his family lived there, apparently in somewhat humble circumstances. Elias prospered in Chilaw. After a time he was joined by his brother Iseris, who says that he left home alone when he was ten years old, though he was probably three or four years older at the time. The two brothers kept a shop or store in Chilaw, in which they seem to have been jointly interested. But it is admitted that the lands in question in this action were the separate property of Elias. At the time when Elias died Iseris was in jail, under sentence of imprisonment for assault and robbery. The property being thus left derelict, possession was taken by officials of the District Court. It must be presumed that such possession was taken for the benefit of the persons rightfully entitled. Iseris came out of jail in December, 1878. Thereupon, or soon afterwards, he entered into possession of the intestate's lands. The circumstances under which the officials of the Court relinquished possession in his favour do not appear in evidence. It seems, however, to be immaterial whether there was an order of the Court on the subject, or whether the officials, who must have known who Iseris was, and must have been aware of his relationship to the intestate, retired in his favour without any specific directions. The Trial Judge says that they were " ejected " by Iseris, but no statement or suggestion to that effect is to be found in the evidence. Some time after the death of Elias, two of his sisters made their way to Chilaw. They seem to have been kindly treated by Iseris, who gave them small sums of money from time to time, and allowed them to obtain provisions from his shop without payment. Indeed, one of the sisters, named Balahami, lived for a long time in a house on Medawatta, which was one of the

- 30. plots or parcels of land belonging to Elias, and part of his estate. In 1907 Iseris by deed settled the intestate's land on his son, reserving a life estate. This action on the part of Iseris was the talk of the neighbourhood. Balahami, who was then the only survivor of the three sisters, became alarmed. Lawyers were consulted. Under their advice Balahami brought an action for partition against Iseris. The action was confined to Medawatta, on the score, it was said, of expense, in order to save the stamp or fee which would have been payable if the whole estate had been the subject of the action. Then Iseris turned her out of her home. Being without means Balahami and other co-proprietors in the same interest sold their rights or claims to the plaintiff Corea, who was Balahami's legal adviser and advocate. He brought this action against Iseris. Iseris's son was afterwards made a party to the action. Iseris in his defence claimed, the benefit of Ordinance No. 22 of 1871, entitled " An Ordinance to amend the Laws regulating the 77 Prescription of Action." It is not disputed that by that Ordinance, or by an earlier Ordinance of 1834, which was repealed by the Ordinance of 1871, the old law was swept away. The whole law of limitation is now contained in the Ordinance of 1871. Section 3 enacts that " proof of the undisturbed and uninterrupted possession by a defendant in any action of lands or immovable property by a title adverse to or independent of that of the claimant or plaintiff in such action. ..... for ten years previous to the bringing of such action shall entitle the defendant to a decree in his favour with costs." The section explains what is meant by undisturbed and uninterrupted possession. It is " possession unaccompanied by payment of rent or produce, or performance of service or duty, or by any other act by the possessor from which an acknowledgement of a right existing in another person would fairly and naturally be inferred. " Then follows an analogous provision in favour of a plaintiff claiming to be quieted in possession of lands or other immovable property under similar circumstances.

- 31. In the present action the plaintiff, Corea, offered some evidence tending to prove that Iseris took out administration to Elias. There certainly was a testamentary case in the District Court relating to the intestate's estate. But the record of the case is missing, and it is not clear whether the case was concerned with an application by officials of the Court, or with an application by Iseris for administration. The District Judge held that it was not proved that Iseris took out administration to his brother's estate. The plaintiffals also endeavoured to prove that Iseris had acknowledged the title of his co-proprietors within ten years of the commencement of the action. On this point also the District Judge was against the plaintiff. Their Lordships accept the decision of the District Judge on these two points. In their Lordship's opinion they are not material to the real question at issue. Assuming that the possession of Iseris has been undisturbed and uninterrupted since the date of his entry, the question remains, Has he given proof, as he was bound to do, of adverse or independent title? His title certainly was not independent. The title was common to Iseris and to his three sisters. On the death of Elias, his heirs had unity of title as well as unity of possession. Then comes the question, Was the possession of Iseris adverse? The District Judge held that Iseris " entered in the character of sole heir or plunderer." " Whichever it was," says the learned Judge, "so he continued, and acknowledge no title in any one else. He has acquired a good prescriptive title " It is difficult to understand why it should be suggested that Iseris may have entered as " plunderer." He was not without his faults. He is described by the learned Judge, who decided in his favour, as " a convicted forger and thief," and " expert not only in crime and incarceration, but also in perjury." But is perhaps going too far 78 to hold that he was so fond of crooked ways and so bent on doing wrong that he may have scorned to take advantage of a good legal title, and may have preferred to masquerade as a robber or a bandit and to drive away the officers of the Court in that character. It is not a likely story. But would such conduct,

- 32. were it conceivable, have profited him? Entering into possession, and having a lawful title to enter, he could not divest himself of that title by pretending that he had no title at all. His title must have enured for the benefit of his co- proprietors. The principle recognized by Wood V.C., in Thomas v. Thomas,1 holds good: " Possession is never considered adverse if it can be referred to a lawful title." The two learned Judges in the Court of Appeal did not adopt in its entirety the suggestion of the Trial Judge. They both held that Iseris entered as " sole heir," and that his title has been adverse ever since he entered. They held that he entered as " sole heir," apparently because he had it in his mind from the first to cheat his sisters. But is such a conclusion possible in law? His possession was in law the possession of his co- owners. It was not possible for him to put an end to that possession by any secret intention in his mind. Nothing short of ouster or something equivalent to ouster could bring about that result. There is no provision in the Ordinance of 1871 analagous to the enactment contained in section 12 of the Statute of Limitations, 3 & 4 Will. IV. c. 27, which makes the title of persons '' entitled as co-perceners joint tenants or tenants in common " separate from the date of entry. Before the Act was passed it was a settled rule of law that the possession of any one of such persons was the possession of the other or others of the co-proprietors. It was not disputed at the Bar that such is now the law in Ceylon. The learned counsel for the respondent, who argued the case with perfect candour, and said all that could be said on behalf of his client, did not, of curse, question the principle on which Wood V. C. relied in Thomas v. Thomas. His submission was that the Court might presume from Iseris's long-continued possession, undisturbed and uninterrupted as it was that there had been an ouster or something equivalent to ouster. No doubt in former times, before the statute of William IV., when the justice of the case seemed to require it, juries were sometimes directed that they might presume an ouster. But in the present case the learned Judge did not make any presumption of that sort. Nor, indeed, did Iseris before this action was brought attempt to rely on adverse possession. His pretence was that he was sole heir. In the first partition action

- 33. he swore that he did not know the name of his father or that of his mother. He swore that Balahami was only a cousin; he knew nothing, he said, about his family, except that he was the only brother of Elias. For this audacious statement he was indicted 1 2 K. and I. 83. 79 for perjury at the instance of the Judge. He was convicted, and sentenced to fine and imprisonment. The Judge who pronounced sentence observed: "It is clear that he was determined to prove that he was the sole heir, and strenuously to deny anything that might count against him." Be that as it may. this is not a case in which the circumstances could justify the presumption of ouster in favour of such a man as Iseris. Their Lordships will therefore humbly advise His Majesty that the appeal should be allowed, the judgment of the Supreme Court and the judgment of the District Judge set aside, with costs in both Courts, and a decree made for partition of the lands which on the death of Elias passed by descent to his heirs. The respondents will pay the costs of the appeal. Appeal allowed.

- 34. TILLEKERATNE et al. v. BASTIAN et al. Prescription-Long-continued exclusive possession by one co-owner- Presumption - Lost grant - Dedication of highway - Ouster - Adverse possession. It is open to the Court, from lapse of time in conjunction with the circumstances of the case, to presume that a possession originally that of a co-owner has since become adverse. "It is a question of fact, wherever long-continued exclusive possession by one co-owner is proved to have existed, whether it is not just and reasonable in all the circumstances of the case that the parties should be treated as though it had been proved that that separate and exclusive possession had become adverse at some date more than ten years before action brought. " THE facts appear from the judgment. Bawa, K.C., and De Zoysa, for appellants.-A co-owner cannot prescribe against other co-owners unless he has actually ousted them, or has by some overt act intimated to them that he is no longer possessing on their behalf but is possessing adversely to them. [SHAW J.-Even if a co-owner possess for 150 years, is he supposed to be possessing on behalf of the other co-owners?] That would not make any difference. Law is not founded on relationship.

- 35. [DE SAMPAYO J.-Must not lapse of time shift the burden?] No. See Corea v. Appuhamy.1 None of the co-owners can prevent the possession of the whole land by one co-owner. [SHAW J.-The. only question is whether a presumption of ouster can be gathered from the length of time.] There is no room for the presumption of ouster here. If an ouster took place it can be proved, as the persons interested are alive and can give positive evidence of ouster. Counsel cited 2 Leader 74; Morgan Digest 21, 169, 273; 7 N. L. R. 91; 10 N. R. 183 (at 186); 3 N. L. R. 213, 137; 7 N. L. R. 91; 1 Cowp. 217; 3 A. C. R. 84; Koch 61 and 42; 1 S C. R. 64; Lightworn on Time Limit of Action 161; Indian Limitation Act 9 of 1908, s. 127; I. L. R. 33 Bom. 317; I. L. R. 35 Cal. 961. The Prescription Ordinance has completely repealed the Roman-Dutch law on the subject. Before Corea v. Appuhamy 1[1 (1911) 15 N. L. R. 65. ] was decided there is no reference in our cases to a presumption of ouster. If there be evidence of exclusive possession for a very long time, and evidence of something which ought to have put the 13 co-owner who is out of possession on his guard, and if he is guilty of gross laches, then there may be prescription. The evidence must be strong and convincing, and that is not the case here. See Brito v. Muthunayagam.1 [1(1915) 19 N. L. R. 38. ] If we introduce the theory of fictitious ouster, the decisions become valueless. E. W. Jayawardene (with him Batuwantudawa), for defendants, respondents.-Whether possession was adverse or not must be judged by the circumstances of each case. In 1893, when Tillekeratne bought the property, he did not enter into possession, nor was the property included in the inventory of Tillekeratne's properties when he declared himself an insolvent. We were allowed to have exclusive and notorious use of this land for forty years, and to take plumbago from it. In 2 S. C. C. 166 it was held that a co-owner cannot dig plumbago without

- 36. the consent of the other co-owners. Counsel cited also S. C. A. C. 8 and 1 C. W. R. 92 and 175. Ouster can be presumed from long and continued possession (2 Thorn. 188; 15 C. D. 87). Counsel also cited 29 Bom. 300; 33 Bom. 317, at 322; 1 S.C. R. 64; Koch 62; 13 N. L. R. 309; 1 Bal. Notes 88; 2 Bal., 40 and 70. Bawa, in reply. Cur. adv. vult. December 16, 1918. BERTRAM C.J.- The facts of this case seem to raise in a very clear and succinct form a question which was discussed, but not decided, in the case of Corea v. Appuhamy. 2 [ 2 (1912) A. C 230 ; (1911) 15 N. L. R. 65.]The decision in that case had a very far-reaching effect. It laid down for the first time, in clear and authoritative terms, the principles that the possession of one co-owner was in law the possession of the others; that every co-owner must be presumed to be possessing in that capacity; that it was not possible for such a co-owner to put an end to that title, and to initiate a prescriptive title by any secret intention in his own mind; and that nothing short of "an ouster or something equivalent to an ouster " could bring about that result. The question was raised in the argument in that case, and discussed in the judgment, whether in the circumstances of the case, even admitting these principles, an ouster should be presumed from the long-continued possession of the co-owner in question. The Privy Council, without negativing the possibility of a presumption of ouster, held that this was not a case in which the facts would justify such a presumption. The questions, therefore, to be decided for the purposes of the present case are:-